U.S. and European Physicians: Medscape Ethics Report 2014

In a fascinating look at differences in medical and patient care ethics between US and European physicians, Medscape reports the results of a survey of over 21,000 physicians, including almost 4000 from Europe. European respondents were from the United Kingdom, Italy, France, Germany, Spain, and 25 other countries. The ways in which US and European physicians see many issues differently reveals much about how diverse cultures view the roles of physicians and patients.

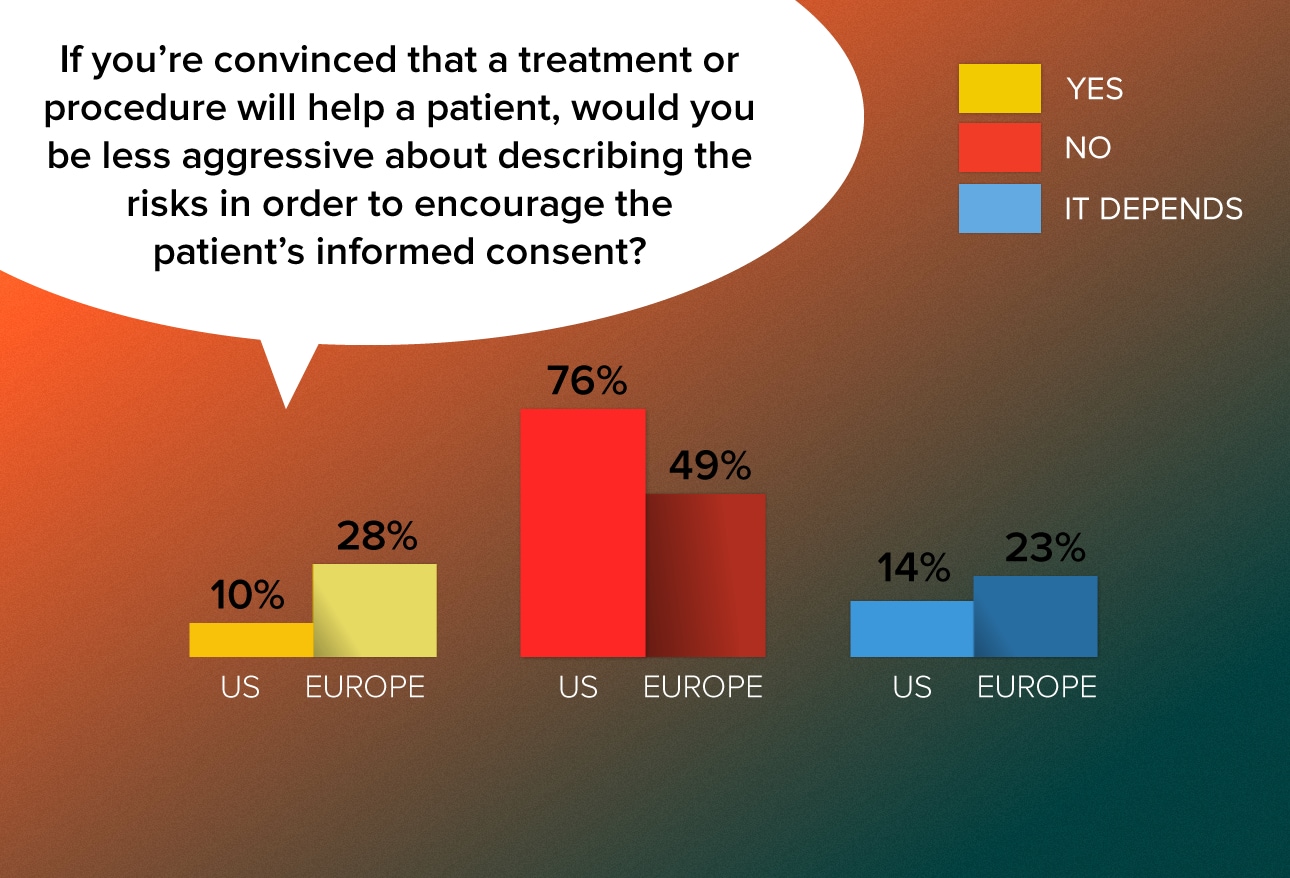

European physicians are more likely than US physicians to downplay the risks of a treatment if they feel that it will help the patient. Dr Kevin Donovan, director of the Pellegrino Center for Clinical Bioethics at Georgetown University Medical Center, attributes the differences to a European ethos that leans toward "weak paternalism," while the American attitude favors "strong patient autonomy." Voicing an opinion expressed by many European doctors, a German pulmonologist said, "Most patients aren't educated or responsible enough to decide all by themselves; they need advice." A UK family practitioner said a doctor should "act as a patient advocate while they are in a stressful position."

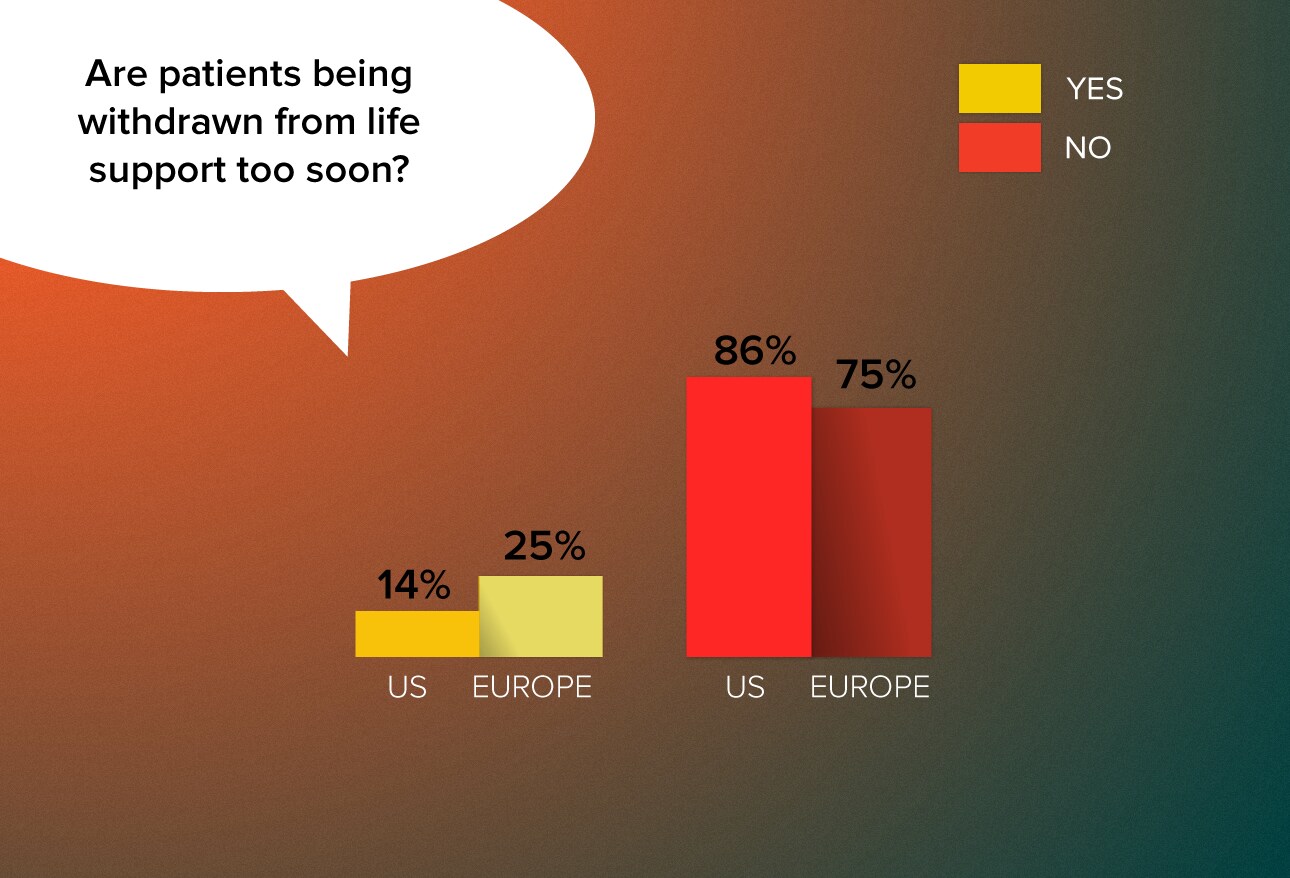

One in four European doctors feel that the decision to remove patients from life support is being made too quickly. Several European physicians said they had personal experience with such cases. "Individual physicians sometimes embrace futility too easily, especially in ITU (intensive therapy unit) settings," writes an Irish neurologist. A UK cardiologist expressed a similar view. "ITU teams seem to be considering withdrawing as soon as some patients hit the unit." Physicians in several countries blamed the phenomenon on cost pressures. "Individual morality is one thing," noted a UK physician. "Running a business is another."

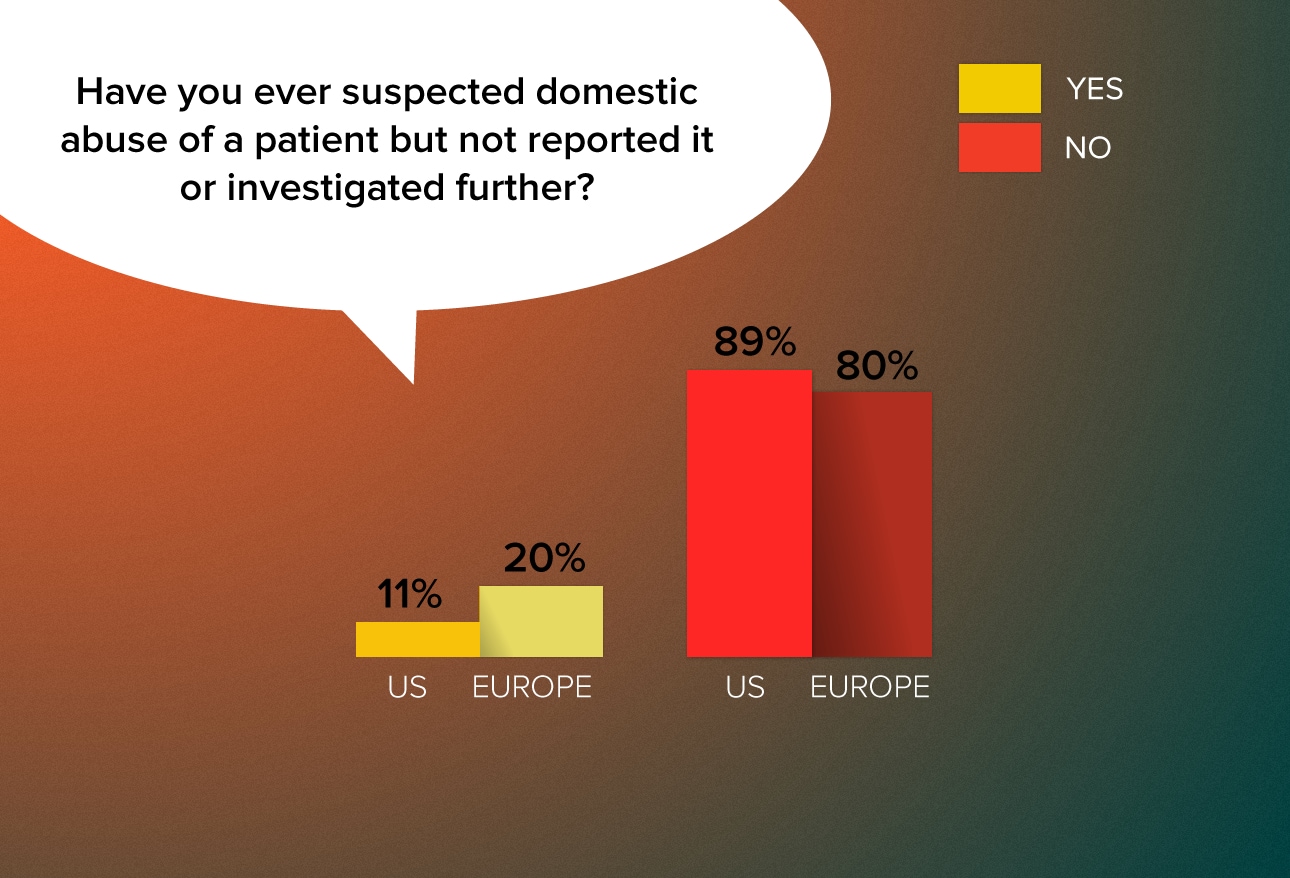

Although most physicians on both continents say they have never suspected abuse without following up, European doctors are almost twice as likely as their US counterparts to have had such an experience. Often those respondents who said they've suspected—but not reported—abuse blamed their inaction on lack of proof. Many European doctors commented that they didn't know how to go about reporting the suspected abuse or said they deferred to a patient who asked them not to report the matter. Others noted that they are reticent to interfere with private matters. "The involved persons seemed to be fine with this situation," recalls a German oncologist, while a UK

family practitioner writes, "Patients do not always respond well to being asked about [domestic violence] and sometimes I have deferred investigating."

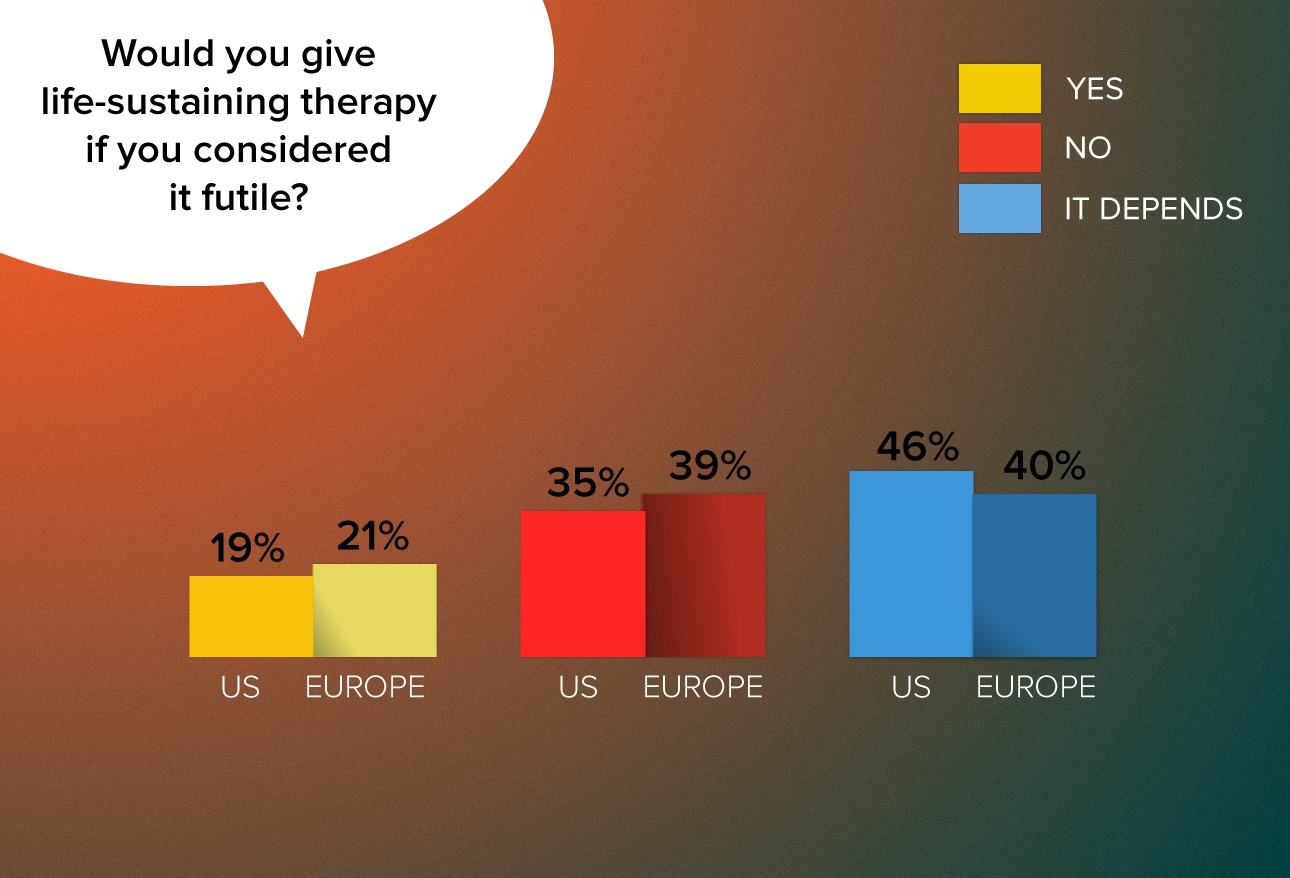

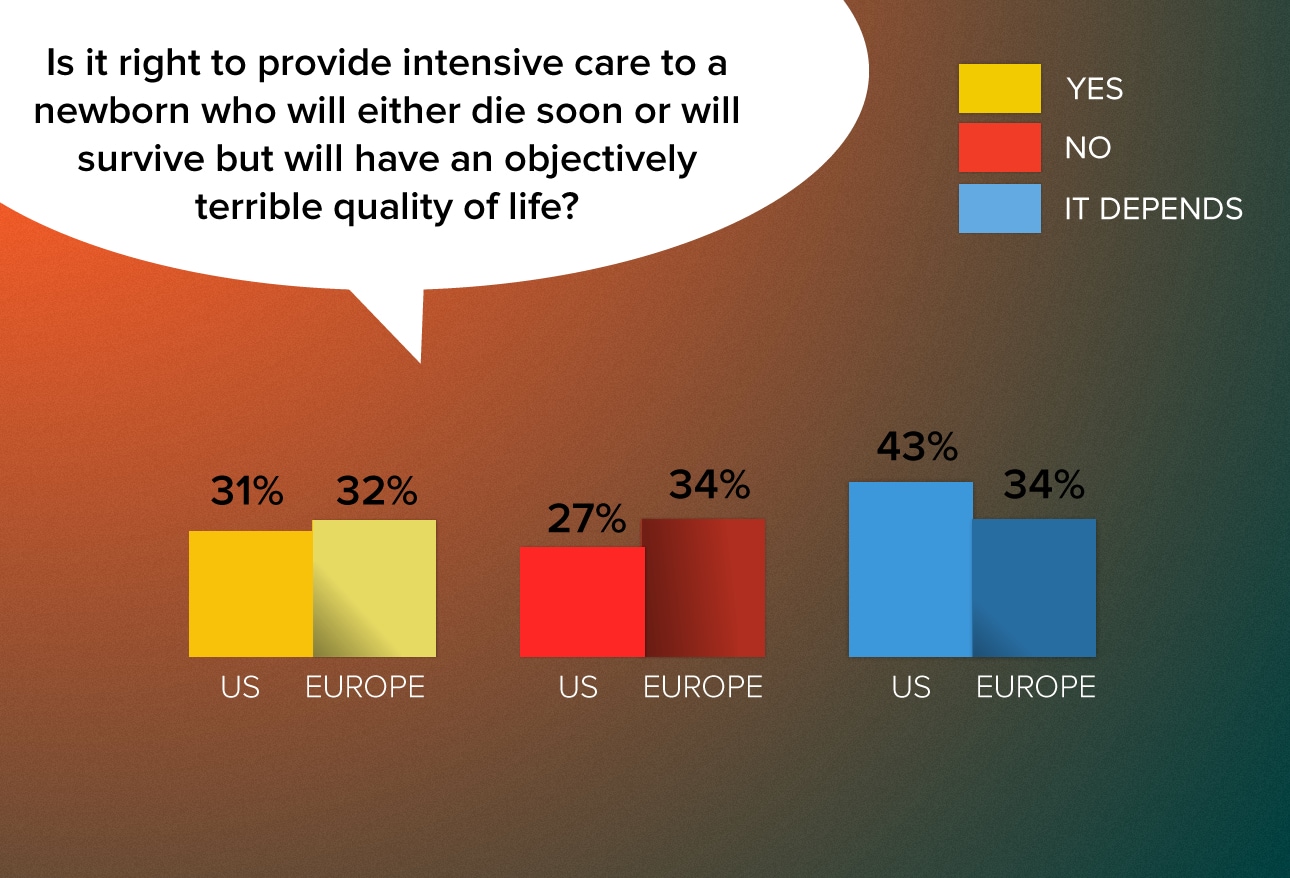

US and European doctors have similar attitudes toward delivering "futile" life-sustaining treatment. Like US physicians, Europeans noted that "futile" is a subjective term that fails to consider compassion. Many doctors noted that they would provide life-sustaining care for a period of time to allow families and patients to come to grips with the situation. "I have been involved in the care of patients where futile treatment is continued whilst working with the parents to bring them to that understanding," noted an Irish physician, while a German neurologist commented that "in very rare situations it seems to be necessary to give prolonged life-sustaining therapy to give the loving relatives a little bit more time to accept the situation."

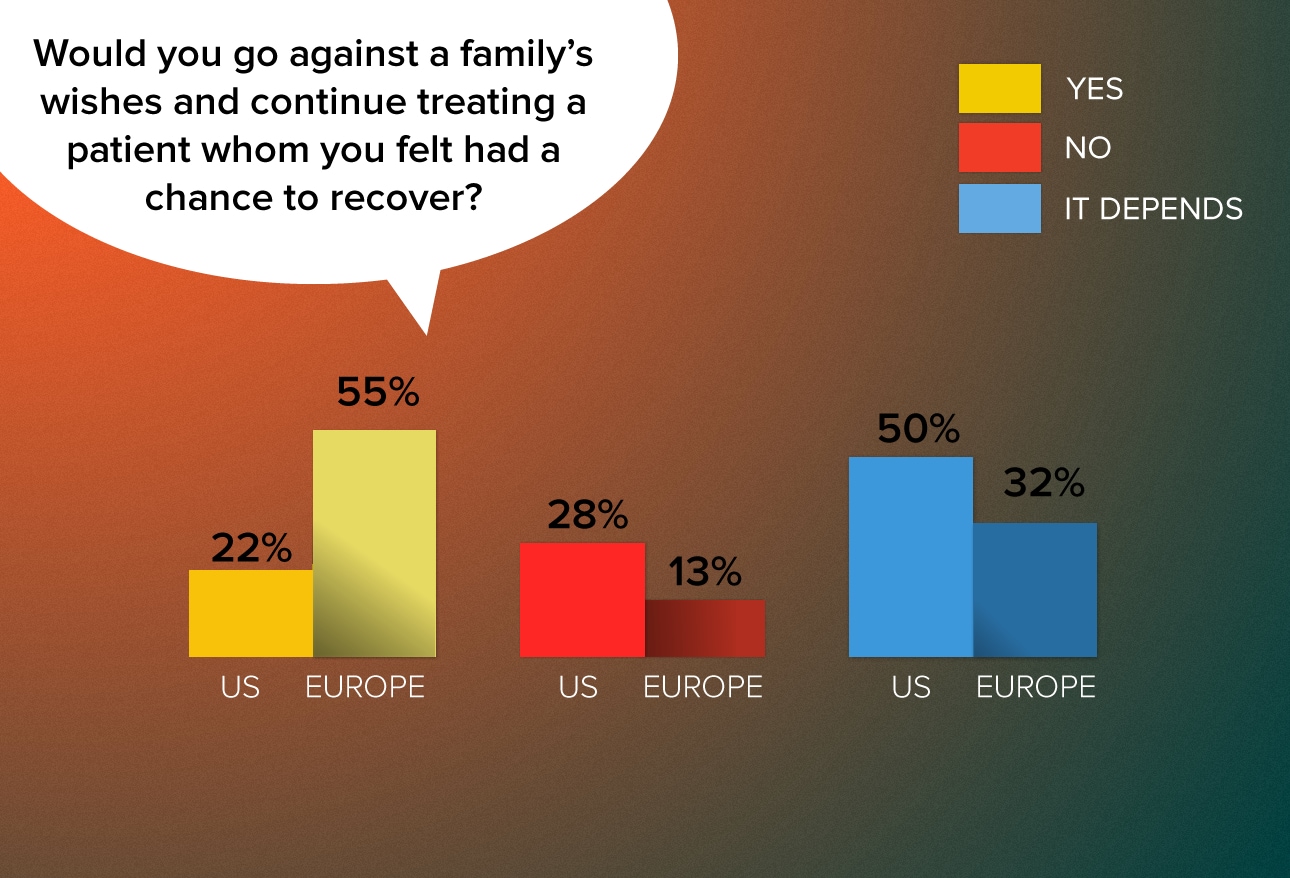

European doctors would be far more willing than US doctors to oppose a patient's family and continue treating that patient if they believed that he or she had a chance to recover. In their comments, European doctors repeatedly noted that "the family opinion matters but they cannot make medical decisions" and that "the wish of the patient counts and nothing else." As a French gastroenterologist noted, "The contract is made with the patient, not with his family." Dr Donovan notes that European doctors' responses indicate that they "give more precedence to their own thinking" than to the opinions of family members.

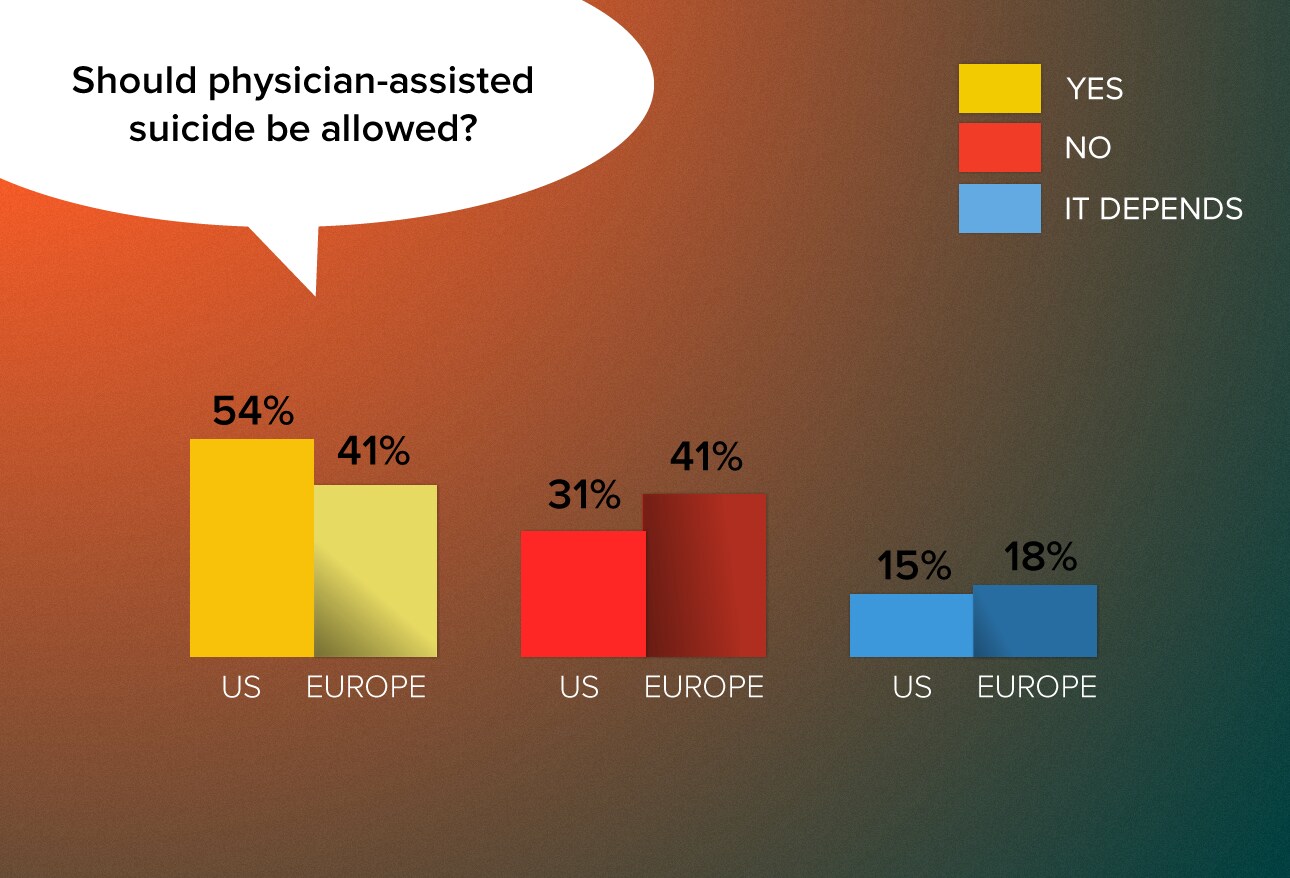

Physician-assisted suicide is hotly debated in the United States and Europe. Five US states have legislation or case rulings allowing aid-in-dying practices, and a handful of European countries either allow physician-assisted dying or enable doctors to prescribe—but not administer—lethal drugs. Although many doctors on both continents say they favor allowing patients to make life-ending choices, they don't want to play a supporting role. As one UK family physician noted, "I do think some people have the right to choose to die but I do not want to be obligated to help, as I think all patients need to know that I will always do my best to save life." Another noted, "Assisted dying may become a valid legal option. However, I believe that we have to create another professional body, but NOT actively practicing physicians, to take on the responsibility for this."

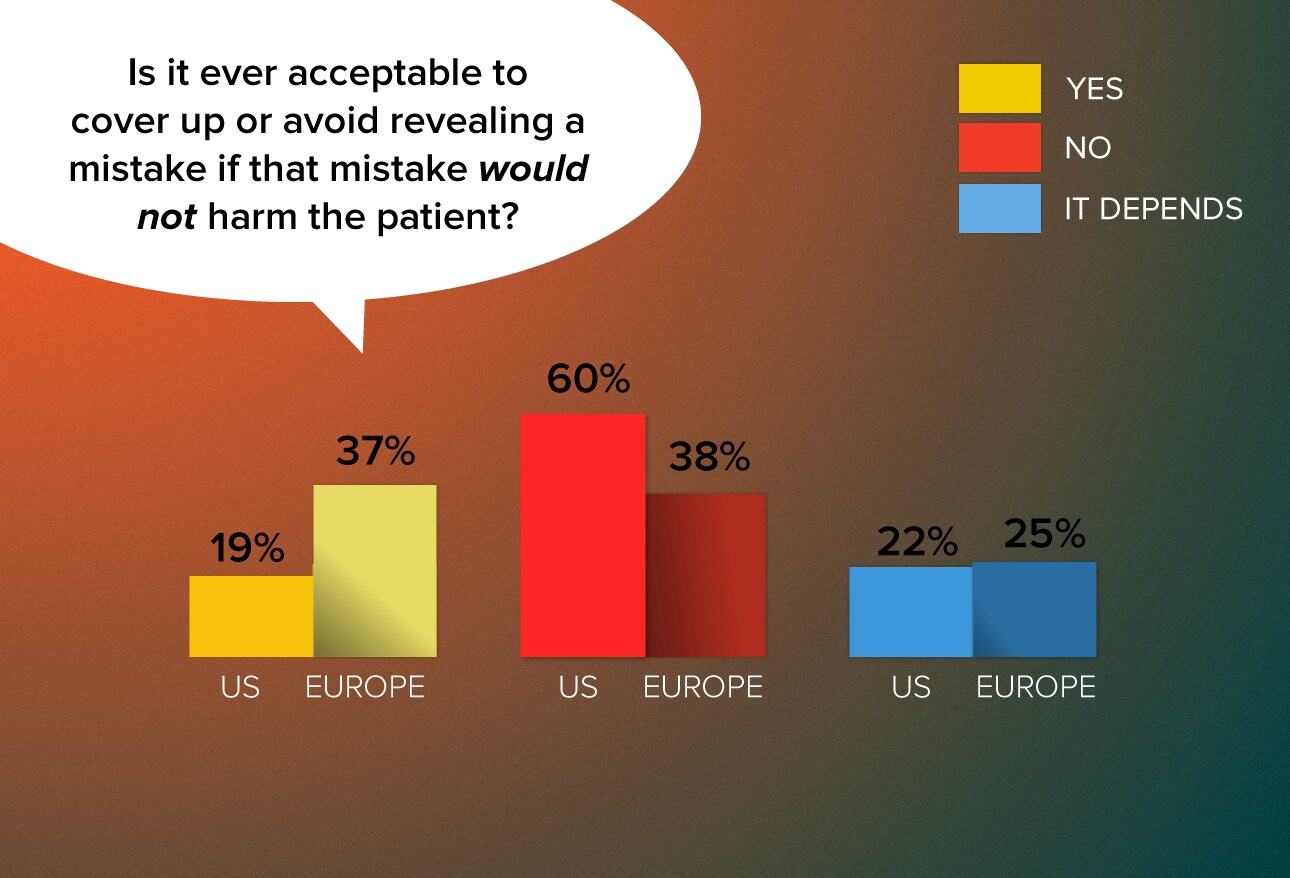

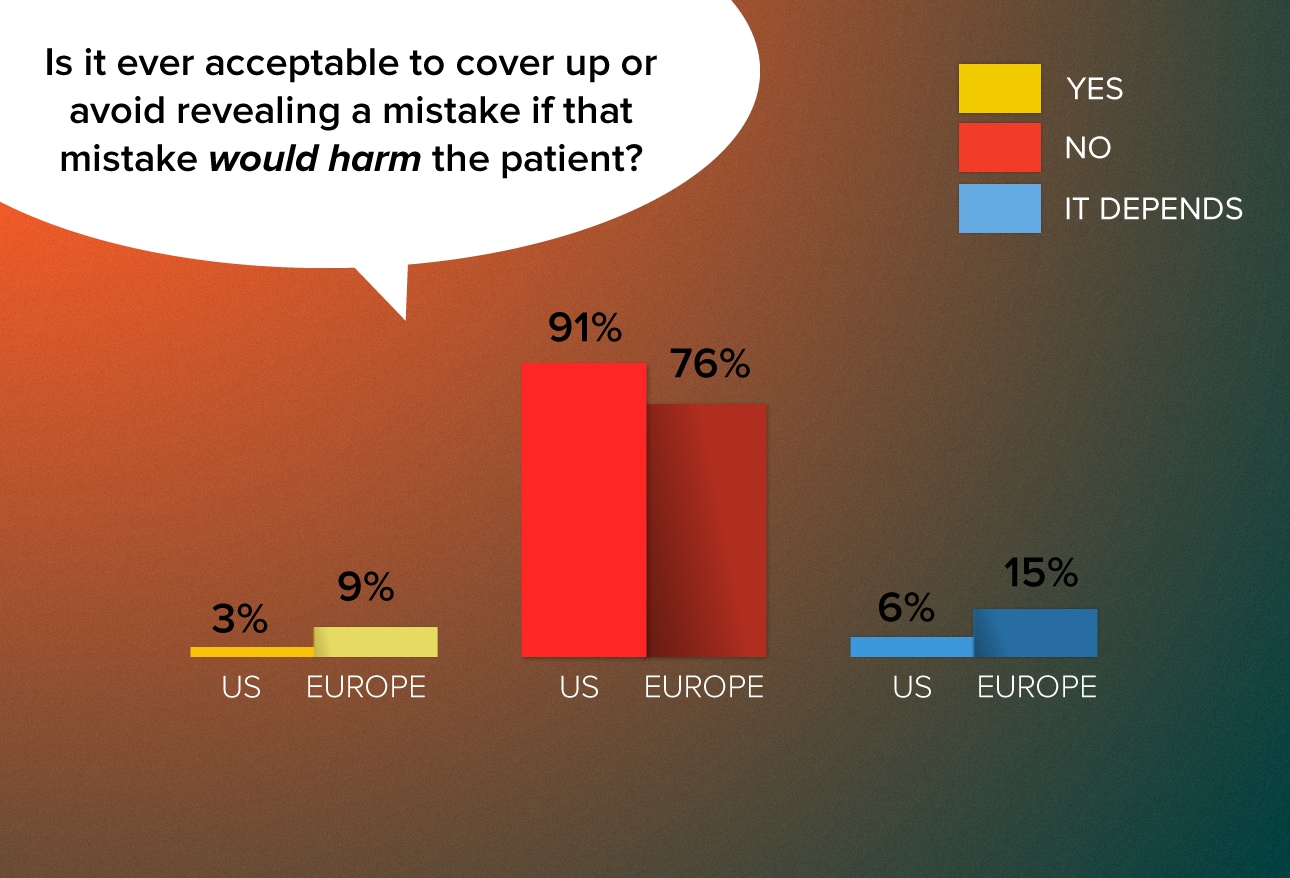

European doctors are far more likely to keep information to themselves concerning a harmless mistake. Some European physicians made light of such situations, noting that no harm was done. "To err is human," wrote a German gastroenterologist, and "it's not important," wrote a French family practitioner. Others, such as a Greek internist, were more defensive, noting that "people make mistakes and lawyers are predators with no concern for the patient." Meanwhile, a Polish neurologist insists, "Mistakes that don't affect the patient's health are a problem of the system, not the patient." Dr Donovan says US physicians' greater willingness to disclose even harmless mistakes probably reflects Americans' deep-rooted appreciation for patient autonomy and possibly a fear of negative consequences that could arise if an undisclosed mistake were later found out.

Nearly a quarter of European doctors—vs 9% of US doctors—say they would or might cover up such a mistake. Revealing the mistake "might cause unnecessary anxiety," noted a Greek oncologist. A Spanish oncologist says informing the patient isn't important but telling people who can prevent the mistake from recurring is. A German rheumatologist insisted that he'd have to consult his insurance company before disclosing an error. As for US doctors, Dr Donovan says their willingness to admit harmful mistakes probably reflects their training. "It's been pretty much drilled into their heads that if you make a mistake that's one thing, but if you are caught lying about a mistake, you are in much deeper trouble."

European doctors were slightly more resolved to not providing intensive care, whereas US doctors were more likely to say "it depends." Many doctors on both sides of the Atlantic who would not provide intensive care cited the child's pain. As a Portuguese family practitioner noted, "This would condemn a child to suffering and this is not acceptable: First, do no harm." US physicians in general expressed a greater willingness to let the parents' wishes shape their treatment decisions. European physicians, conversely, were more likely to cite scarce resources and societal burdens as reasons not to treat. "Providing (treatment) for this child may deprive a baby with better prospects of getting treatment," wrote a UK family practitioner, while an Irish doctor wrote, "I think that if parents decide that they must have treatment, then they should be willing to pay themselves. That child will be a drain on resources all its life. Sounds harsh but it's true."

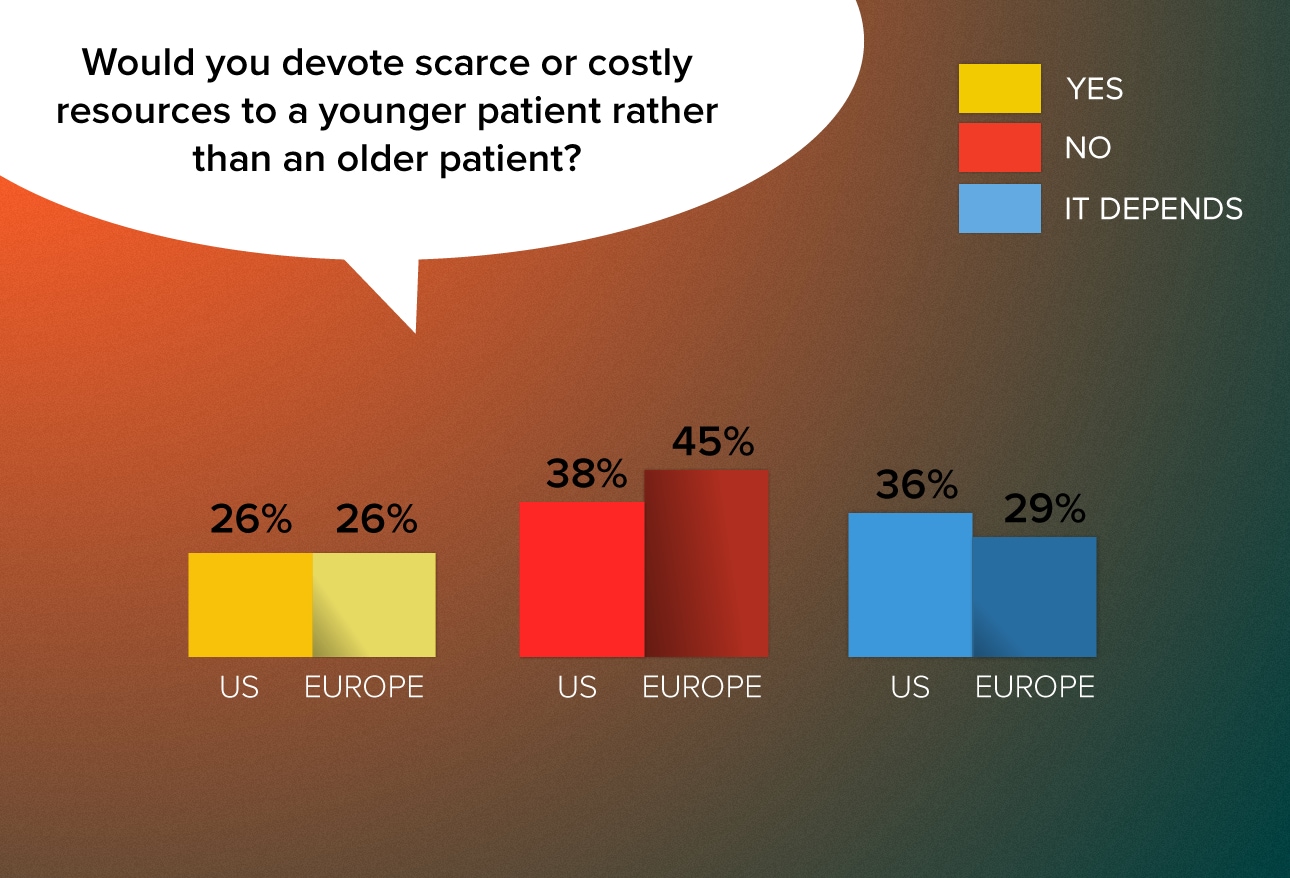

European doctors were more likely than US doctors to say they would not make such an age-based allocation. In explaining their decision, European doctors, including a UK psychiatrist, noted, "Life has an absolute value, not a 'productivity years' value." Dr Donovan noted that the responses could reflect the values of a

youth-oriented culture in the United States but might just as likely depend on the age of the physician respondents.

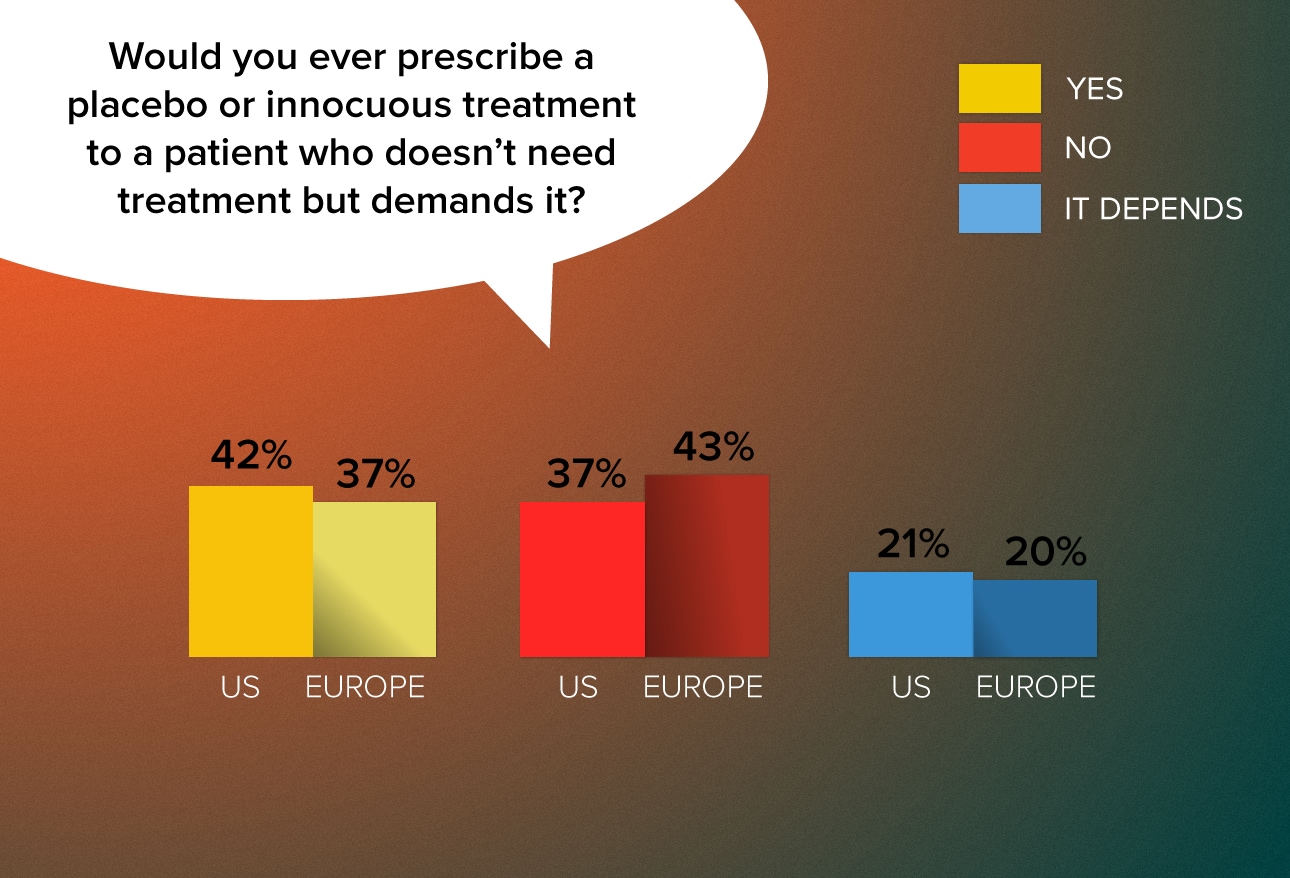

While US doctors' responses to most questions generally reflected a greater deference to patient autonomy than European doctors', US physicians are slightly more willing to prescribe a placebo. A number of doctors on both continents cited the placebo effect as rationale for prescribing an innocuous treatment, but European doctors seemed befuddled by the question: "More important to explore why patient is insisting," wrote a UK hematologist, and "What's the point?" asked a UK family practitioner. "As doctors, we have to have difficult conversations about care and treatment all the time. Why duck this one?" Many US doctors cited patient satisfaction and time constraints as rationale for prescribing placebos.

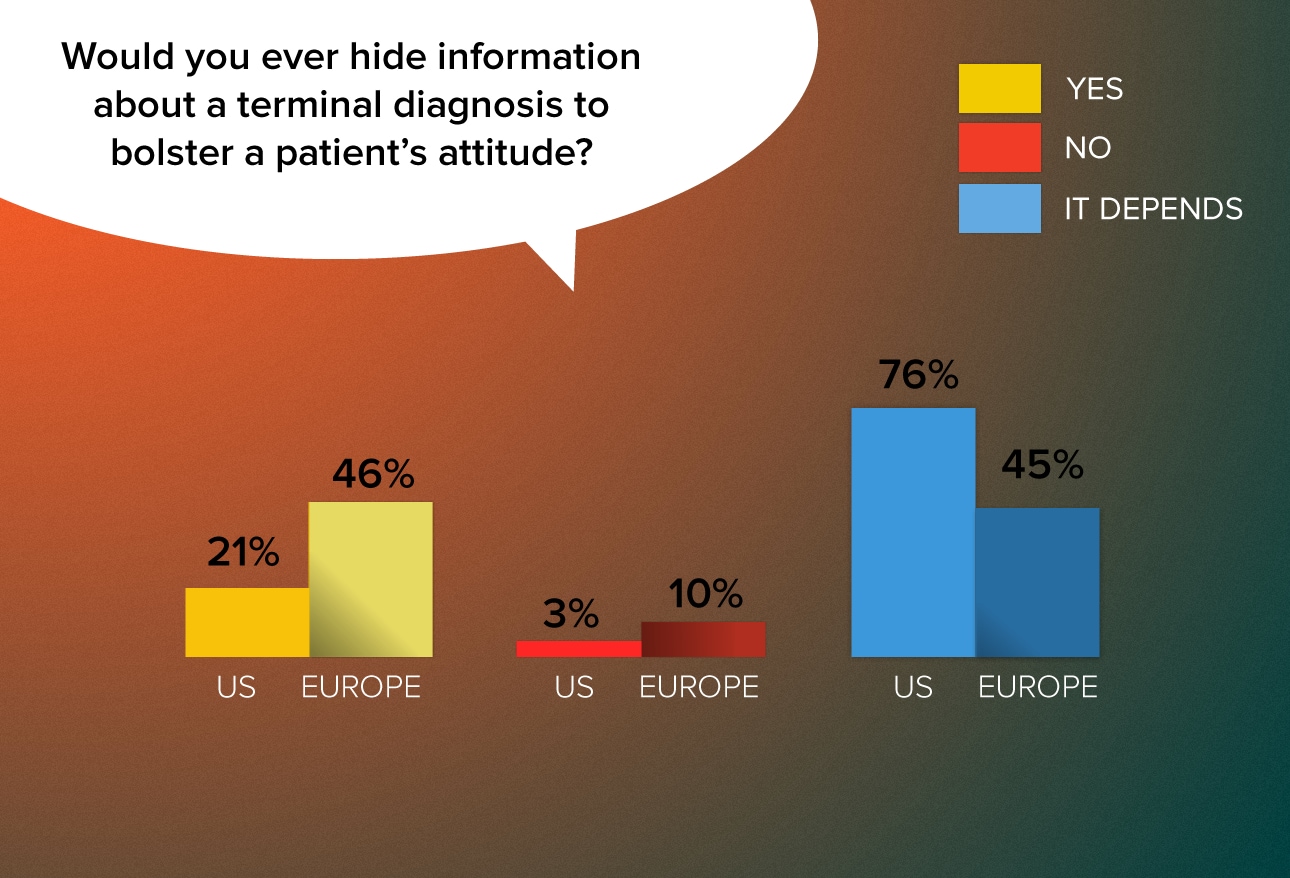

US doctors are more forthright with their patients when delivering bad news. But many European doctors wrote that they take an incremental approach to delivering news of a terminal illness. "When I had to deal with such problems, I tried to give full information progressively so it could be integrated step by step if the context made this possible," writes a Swiss psychiatrist. "I always tell my patients what they have, but the form and the time to transmit the news make all the difference," notes a Portuguese neurologist. "I say everything by steps and with carefully chosen words." While insisting that he never lies to a patient, a Spanish physician says he "manages information as a process."

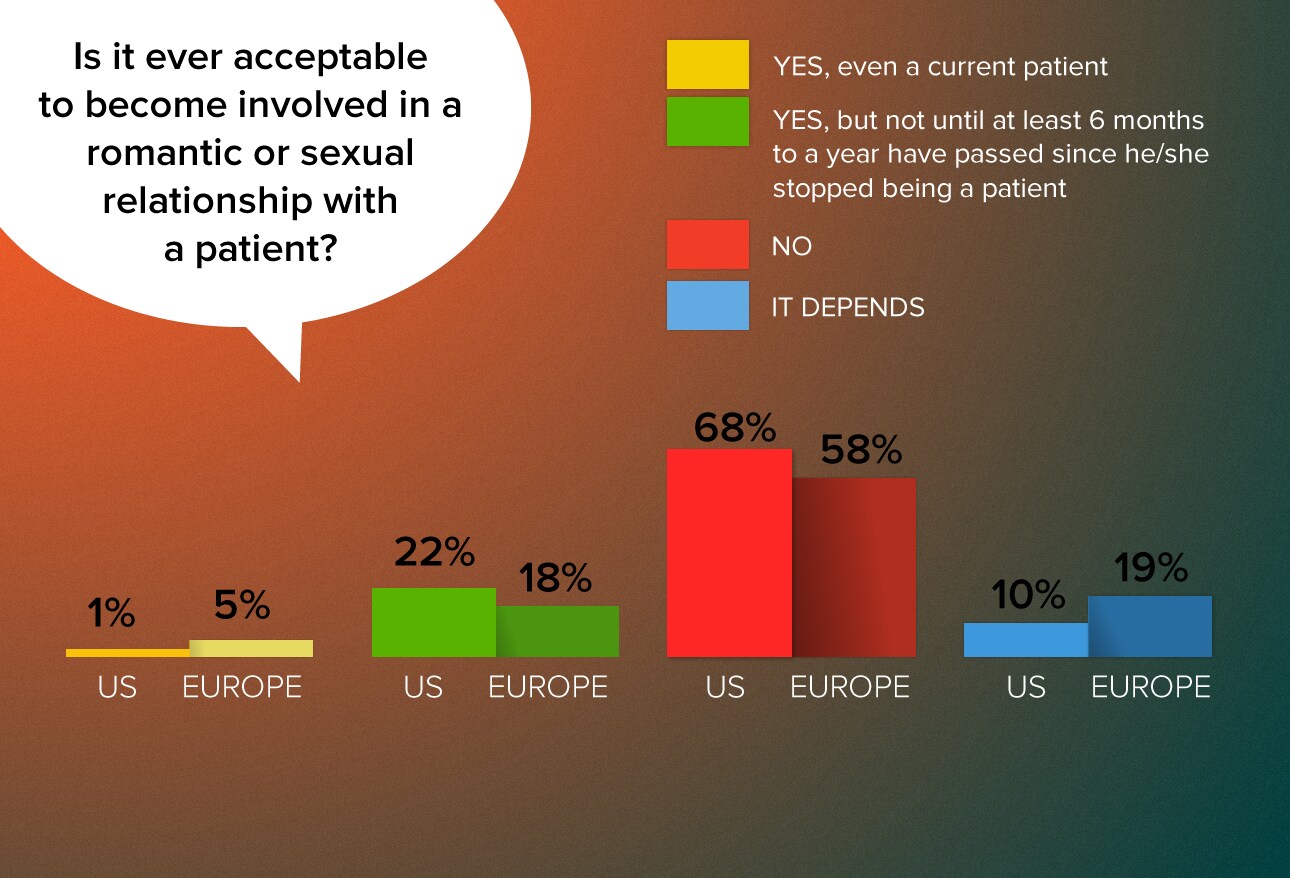

While only a tiny minority of physicians say that it's acceptable to become romantically involved with a current patient, that minority is larger in Europe than in the United States (5% vs 1%). European physicians are likewise more open to the possibility of becoming involved with a patient or a former patient, with 42% saying it would or might be acceptable vs 33% of US doctors. According to Dr Donovan, those differences probably reflect broader cultural a attitudes about romance—"grownups take responsibility for their behavior," writes a French family practitioner—as well as different legal climates. "Only a fool would take the medical-legal risk," wrote a US physician.

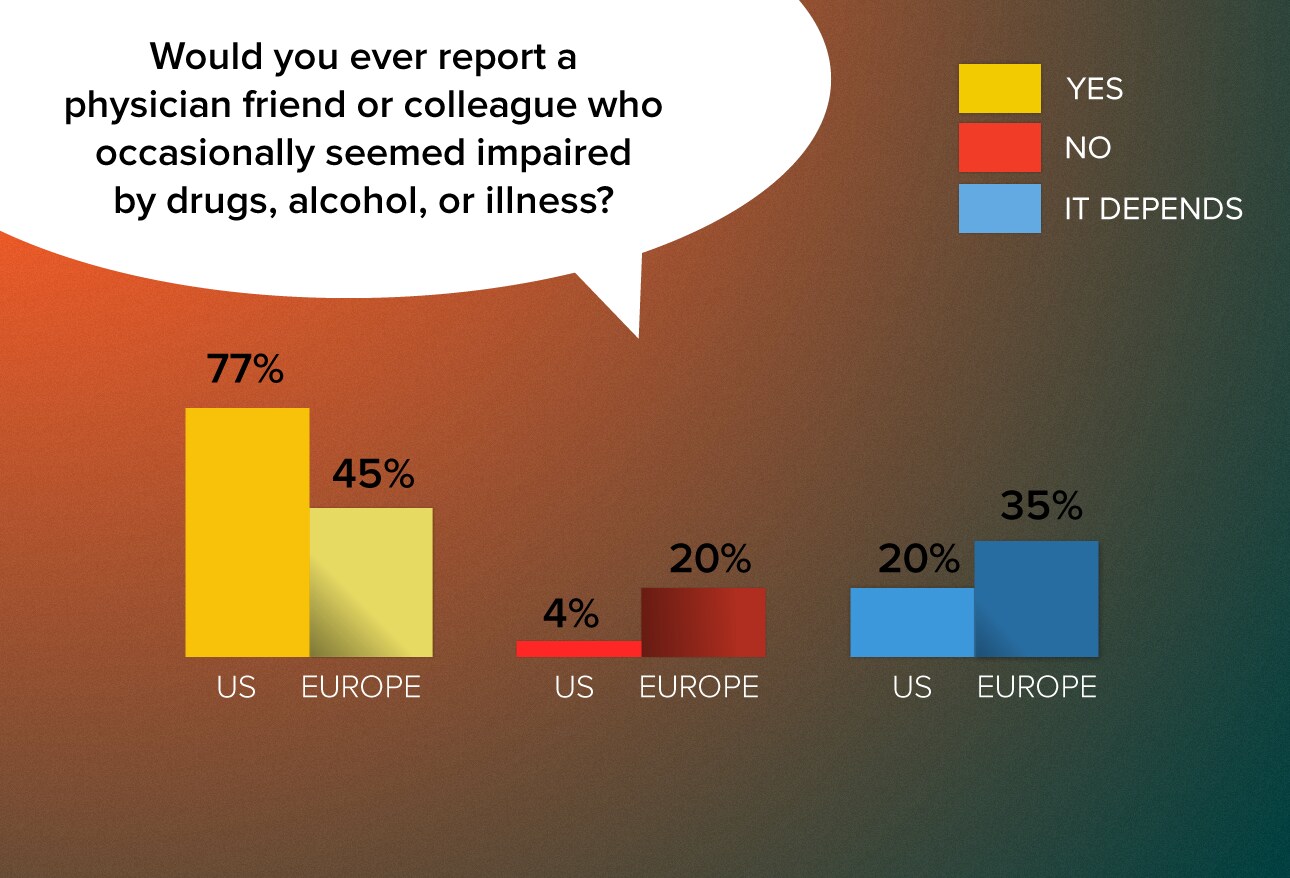

European physicians are far more likely to say they would not report an impaired colleague. A French family practitioner notes that he would not report a colleague "out of professional solidarity. The furthest I'll go is to advise his patients to postpone any care with him as long as this tough time lasts." Other European doctors said they would first talk to a colleague about the problem. Dr Donovan attributes the difference to a movement in recent decades "to define and address professionalism in the US. One of the hallmarks of professionals is that they hold their members to a standard and they police themselves. It should be reassuring to American patients that their doctors feel strongly about doing this."

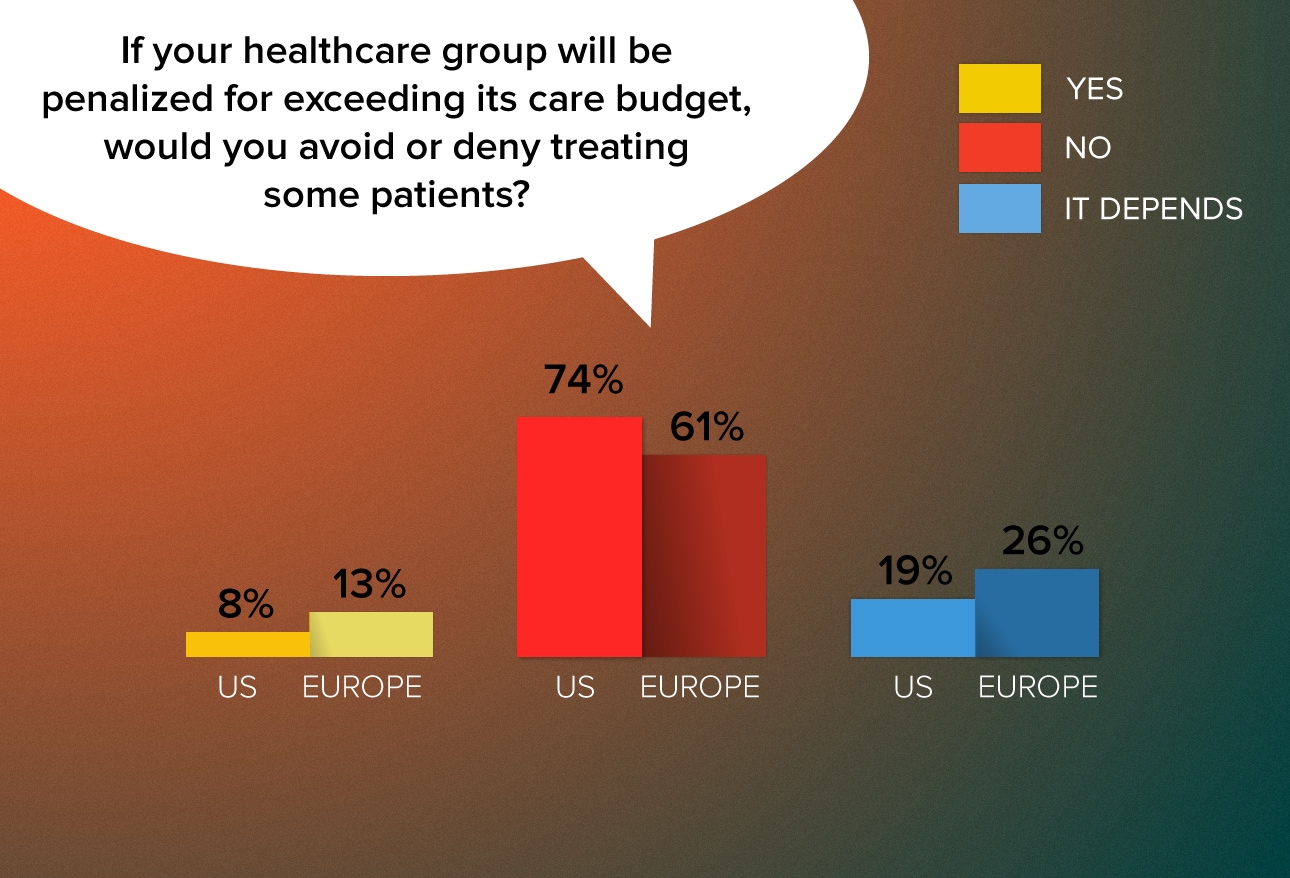

European doctors are more likely than US doctors to deny care on the basis of their organizations' budgets. Those who would deny care note that they do so only "because I am forced to" and recognize it as a necessity to ensure future service. As an OB/GYN in Greece noted, "If the organization gets a penalty, more patients will be deprived from treatments the following year." While denials are difficult, many physicians note that they would try to minimize the impact on patients by only denying treatments they considered to be of "low value" or ones that are "not immediately necessary or can be done somewhere else."

http://img.medscapes...thics/fig17.jpg

A large percentage of physicians on both continents are open to the possibility that they might at times need to withhold information from a patient at a family member's request. A similar share of US doctors (61%) and European doctors (64%) say they would or might withhold information. Dr Donovan notes that doctors' willingness to withhold certain information probably reflects an important understanding of and respect for certain cultural mores. "In some cultures," he notes, "bad news must be delivered by certain individuals, such as a family member, and it would be considered very rude for a doctor to deliver the news.

http://img.medscapes...thics/fig18.jpg

European doctors are more hesitant to say that unhealthy behaviors should come with a price tag. That may be because their healthcare systems are predominantly state supported, making it difficult for them to envision how such policies could be implemented, says Dr Donovan. Yet, several doctors noted a fundamental objection to penalizing patients for their behaviors. "Addictions are a serious issue no matter the drug (tobacco or food)," writes a Greek internist. "Should we not bill the companies who advertised and/or who continue to make cigarettes or sell sugary drinks?" asks an Irish oncologist. "What would be next: insurance premium depending on our genetic profile?" protests a Dutch internist. A UK pulmonologist notes, "I am not here to be judge or jury about behaviors but to treat people and provide advice regarding the healthiest way to live."

http://img.medscapes...thics/fig19.jpg

Asked whether they would perform an abortion if it were against their beliefs, slightly more doctors (in both the US and Europe) say they would. A significant percentage of doctors on both continents (41% US, 36% Europe) say they would not. Most doctors on both continents came down firmly in the "yes" or "no" categories rather than voicing an ambivalent "it depends." Dr Donovan says those firm responses reflect the fundamentally divisive nature of the issue itself. "The answers really reflect how polarizing the issue is, particularly in the United States."

http://img.medscapes...thics/fig20.jpg

Roughly 40% of doctors on both continents felt that late-term abortions should not be legal. Nearly the same number felt that the decision would have to depend on the circumstances. Many physicians on both sides of the ocean invoked the heated rhetoric that frequently characterizes the abortion debate, but a large number focused exclusively on situations where the fetus was not viable or the mother's life was at risk. "Only for medical reasons," noted a German urologist.

http://img.medscapes...thics/fig21.jpg

Most European doctors favor random testing for drug and alcohol abuse, while the largest share of US respondents is against the idea. Dr Donovan notes that this question relates to the subject of physician autonomy. A German doctor sees the topic as "a matter of public safety," and a French pulmonologist notes that many other professionals are subject to such testing. An Italian physician notes, "As a profession we have the highest rates of depression, suicide, divorce, alcoholism, and substance and drug abuse. Random testing might make us wake up and stop thinking of ourselves as moral arbiters." But many US doctors call the idea "Big Brother" and say it would add to dissatisfaction with the practice of medicine. "Americans simply don't like their autonomy restricted," says Dr Donovan.

http://img.medscapes...thics/fig22.jpg

Edited by chieftecs, 01 May 2015 - 11:50.