Zar ta firma jos postoji?Vrijeme je da zamjenis tu Nokiu 3310 za neki smartphone. Znam ja da ti volis retro stvari, ali moras u korak sa vremenom.

BlackBerry PRIV :-P

Whisk(e)y

#541

Posted 25 February 2017 - 08:44

#542

Posted 25 February 2017 - 17:02

#543

Posted 25 February 2017 - 17:40

Nista drugo nemam vec 8 ili 9 godina. :-)

Tako je druze, najbolji telefon iz najbolje zemlje, pravljen za americhke predsednike i vrhunske intelektualce. ![]()

#544

Posted 28 February 2017 - 10:23

Since 2013 Scotland has welcomed 14 new whisky distilleries, from Harris in the Outer Hebrides down to Glasgow in the Lowlands.

Two distilleries fired up their stills for the first time in the last 12 months alone: InchDairnie in Fife began production in May, making two different single malts, while Torabhaig on the Isle of Skye became operational in December.

As we move into 2017, investment in Scotch whisky is only expected to continue, with 20 new distilleries projected to open within the next 24-36 months, including Edinburgh’s first malt distillery in 92 years, Islay’s ninth distillery and Arran’s second.

This year alone will see the launch of at least seven new distilleries, as well as the regeneration of a silent Lowland favourite.

It will also be a year of firsts – the first distillery in the Borders for 180 years, the first legal distillery on the Isle of Raasay, and the first distillery to be launched solely by a woman.

While their whisky won’t be available for several years yet, the anticipation of the next wave of Scotch distilleries opening in 2017 should whet more than a few appetites.

BLADNOCH DISTILLERY

It’s been silent since 2009, but this year will see the return of Scotland’s most southerly distillery under its 11th owner. Bladnoch has a chequered history of takeovers, renovations and long silent periods – the distillery was first erected in 1817 on the McClelland farm in the hamlet of Bladnoch in the south-east of Scotland, and since that time has seen 10 owners come and go. In 2015 it was purchased by Australian yoghurt entrepreneur David Prior, who has completely renovated the site with the intention of producing malt spirit by May 2017 – just in time to celebrate Bladnoch’s 200th anniversary.

Find out more about Bladnoch distillery.

BORDERS DISTILLERY

July 2017 will be a momentous month for the people of Hawick, as the town welcomes the first malt whisky distillery in the Borders for 180 years. The £10m Borders distillery, situated in a former factory in Hawick town centre, will have the capacity to produce up to 1.8m litres of spirit per year. While we’ll have to wait some time for the first malt whisky release, expect a Borders gin, made using local botanicals, in the near future.

Find out more about Borders distillery.

CLYDESIDE DISTILLERY

Glasgow was once a booming whisky distilling and blending hub, but by the start of the 21st century production in the city had reduced to a murmur, the only whisky distillery in operation being the Chivas Brothers-owned Strathclyde grain plant.

In 2014, after an absence of 112 years, malt whisky distilling returned to the city with the opening of the Glasgow distillery in Hillington. Meanwhile, the construction of a second, independent distillery was also under way at the historic Queen’s Dock. Morrison Glasgow Distillers (MGD), led by whisky veteran Tim Morrison, plans to transform the old 19th-century Pump House into a £10.5m single malt distillery named Clydeside.

Situated in the heart of Glasgow’s famous docks, the distillery will open this autumn, featuring a café/restaurant and ‘interactive whisky experience’ with tours and tastings offered to the 65,000 visitors expected every year. While Clydeside’s malt whisky is expected to be light and fruity in the typical Lowland style, MGD has hinted at a spicier Speyside style to reflect Glasgow’s former glory days of tobacco and spice shipping.

Find out more about Clydeside distillery.

DORNOCH DISTILLERY

March 2016 saw brothers Simon and Phil Thompson launch a crowdfunding campaign to transform a 135-year-old fire station into a microdistillery. The directors of the family-owned Dornoch Castle Hotel in Sutherland were overwhelmed with pledges and eventually obtained their licence to distil in December. The brothers have been running test mashes, fermentations and distillations, but won’t complete a run of spirit to lay down as single malt whisky until early 2017. Their plan is to eventually produce a ‘traditional’ malt spirit made using heritage varieties of floor-malted barley, brewers’ yeast, long fermentations in oak washbacks and direct-fired distillation.

Find out more about Dornoch distillery.

DRIMNIN DISTILLERY (NAME TBC)

Along with being a working farm, holiday accommodation provider and wedding venue, the historic Drimnin Estate in Argyll is also set to become a distillery early this year. Drimnin's distillery – the name is yet to be confirmed – is run separately to the estate but will occupy the farm steadings adjacent to Drimnin House, and will ‘explore the limits of what whisky from Scotland can be’. An on-site visitor centre will offer tastings and tours, including lunch in a converted greenhouse with ‘spectacular’ views of Tobermory and Mull.

ISLE OF RAASAY DISTILLERY

This year sees the first legal distillery launch on the Hebridean island of Raasay. It’s the first of two new projects for R&B Distillers, the second of which will eventually be a site in the Borders. For now, Isle of Raasay distillery – which is expected to be operational by the summer – is expected to produce a signature whisky with a fruity, sweet and lightly peated character, as seen in its pre-emptive release, Raasay While We Wait.

However, the distillery’s configuration allows for plenty experimentation with fermentation in distillation, allowing for a variety of styles. Yes, there will be a visitor centre – the island is just a hop away from Skye and its two distilleries (Talisker and Torabhaig) – complete with overnight accommodation for members of the distillery’s Na Tusairean whisky club.

Find out more about Isle of Raasay distillery.

LINDORES ABBEY DISTILLERY

The first recorded mention of Scotch whisky is in the Exchequer Rolls of 1494, where Friar John Cor is asked to make aqua vitae for King James IV. Cor is reputed to have resided at Lindores Abbey in Fife, a now derelict building often referred to as the ‘spiritual home of Scotch whisky’. Now, some 500 years later, distilling is set to return to the area – across the road in fact – at Lindores Abbey distillery, with a mixture of traditional and modern production processes.

Barley will be mostly sourced from the 60 acres of farmland surrounding the site, with some dried using peat. The distillery will feature a modern, on-site warehouse with partly-heated sections allowing the team to experiment with speed of maturation. The distillery is set for completion in September 2017 and, while its first whisky won’t be ready for some time, Lindores Abbey will release an unaged aqua vitae later this year.

Find out more about Lindores Abbey distillery.

TOULVADDIE DISTILLERY

Construction is yet to start at this microdistillery situated at the Fearn Aerodrome near Tain, but Toulvaddie is expected to be operational by May this year. Somewhat unbelievably, considering the long history of distilling in Scotland, it will be the first whisky distillery founded solely by a woman.

Heather Nelson – who will fund and operate the distillery herself with the assistance of a brewer – intends to produce a light, ‘easy-drinking’ whisky in the style she likes to drink, with both peated and unpeated expressions eventually available. A limited number of 70-litre casks to be filled in Toulvaddie’s first year are already available to purchase for £2,000 each, while whisky incentives are available to those wishing to join the Distillery Founders’ Club.

#545

Posted 02 March 2017 - 09:08

THE WHISKY BARONS: WHO WERE THEY? 01 March 2017 by Dave Broom

To simply sum-up the Whisky Barons as ‘entrepreneurs’ would be doing them a disservice. For these were the men who laid down the cornerstone of the Scotch whisky world as we know it today. Dave Broom investigates.

Whisky Barons: James Buchanan (left) and Tommy Dewar (right) were ‘celebrities’ in their dayScotch whisky was built thanks to the work and efforts of a group of remarkable men. They are often called ‘entrepreneurs’, but they were considerably more than that – they were visionaries, creative, financially astute, open to possibilities, risk takers, men of action. By the 1920s, many of them had been ennobled. Collectively, they became known as the ‘Whisky Barons’.

The Barons’ ascent from obscurity to the upper reaches of society was extraordinarily rapid, but it mirrors that of Scotch.

John Alexander Dewar was only 24 when, in 1880, he took over the firm his father had founded. He was joined by his younger brother Thomas (aka Tommy) who was 21 at the time. While John Alexander stayed in Scotland, Tommy was sent to London to try and establish the firm’s whiskies in what was still a very new and untested market.

By 1899, Dewar’s was selling more than one million gallons a year. Three years later, Tommy (along with his friend and fellow confirmed bachelor, Tommy Lipton of tea fame) was knighted in the accession honours of King George V. In 1907, John Alexander was made a baronet and in 1917 was ennobled as Baron Forteviot of Dupplin, Perth. Tommy had to wait for two years to become Baron Dewar of Homestall, Sussex.

James Buchanan’s story runs parallel to Tommy’s. The Canadian-born Scot started his whisky life as London agent for Mackinlay’s in 1879. In 1884, he had started his own firmand within a decade, the ‘Buchanan Blend’ was a national success and eyeing up global expansion. He was made a baronet in 1920 and became Baron Woolavington in 1922.

The last of the barons is strangely, and sadly, forgotten. His name was James Stevenson, who joined John Walker & Sons at age 15 in 1888. Sent to London in 1908 to run its business there, he became joint managing director in 1912. He was made a baronet in 1917 and became Baron Stevenson of Holmbury in 1924.

It all seems relatively straightforward. Success of brands rewarded with honours. The story behind the titles is, however, more complex. Not all of the Barons got their titles for services to whisky. John Alexander’s came for services to politics. He had served as Lord Provost of Perth and was the Liberal MP for Inverness between 1900 and 1916 (Tommy too was a politician, but only served as Conservative MP for St Georges in the East for one term).

Celebrity style: James Buchanan was a well-dressed, ‘A-list’ celeb in his day, as this sketch from Vanity Fair shows

Buchanan, while not a politician, was a noted patriot and received his baronetcy for services to the war effort. The same applied to Stevenson, who after the outbreak of war in 1914 volunteered his services to the Government, for no remuneration. He served under Lloyd George, the Minister of Munitions. Post-war, he became commercial advisor to Winston Churchill, Secretary of State for the Colonies and chaired the committee which organised the British Empire Exhibition in 1924.

The honours show quite how far Scotch had moved, from the rough, rude, drink of North Britain to an acceptable middle class tipple in polite London society.

It is hard to imagine quite what it would have been like; the arrival of this new drink, sold by remarkable salesmen who were assiduous in ensuring that the glasses ended up in the right hands.

They didn’t just sell whisky, they sold an idea, and in doing so created this new concept called ‘branding’. By being seen in the right theatres, race meetings, sporting events, hotels, clubs and restaurants, they built whisky’s credibility as an acceptable drink for gentlemen, because they were seen as gentlemen themselves.

The dapper and elegant Buchanan didn’t just have the contract to supply music halls. In 1898, he had acquired a Royal Warrant from Queen Victoria. The year before, he had been given the exclusivity to supply the House of Commons. To quote Figaro magazine of that year:

‘All orators and all persons who require to make use of their voice have adopted in this country, this drink [whisky and water].’

Tommy Dewar was equally well connected. Like Buchanan, he was an incredible salesman who saw the importance of advertising, but he also realised the benefit of making himself a celebrity and cultivating links with the right people.

King Edward VII gave him a knighthood, not for whisky or politics, but because he was a personal friend. The King had the first car in Britain, Tommy Lipton the second, and Tommy Dewar the third. Whisky men had the ears and lips of princes, and in class-obsessed Britain of the time that was a seal of approval.

‘Don’t forget,’ said Diageo’s Nick Morgan when we were discussing the Barons, ‘they were celebrities. Buchanan and Dewar were “A-list” of their time. Buchanan was the third-richest man in the country at the time.’

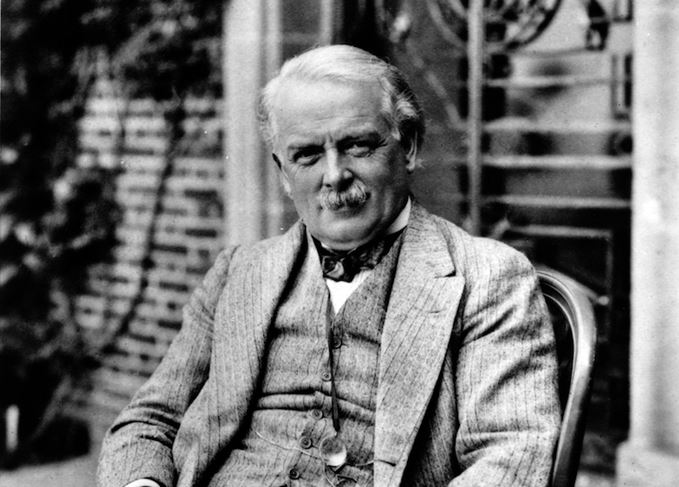

Friends in high places: Tommy Dewar was the third person to own a car in Britain (photo: Dewar's Archive)

It could also explain some of the apparent anomalies in the distribution of honours. James Stevenson’s was entirely for his political work. Alexander Walker, too, was knighted for his efforts during the conflict, but was never made a peer. The Walkers were quieter men, their manner of doing business less publicity-oriented than their rivals: ‘Less promiscuous with their wealth,’ as Morgan phrases it.

The same could well apply to Peter Mackie, of White Horse, another of the whisky knights of 1920. ‘If the honour was conferred on him for his success in the whisky trade,’ wrote Robert Bruce Lockhart in Scotch, ‘he must have been gratified, for of all the whisky magnates he was the most ruthless in his rugged individualism and the proudest of his own achievement.’ For all of the technical advances he brought to whisky, ‘Restless Peter’ never quite fitted in.

All of this also brings into perspective how significant the Great Merger of 1925 was, when Buchanan-Dewar (which had merged in 1915) and Walker joined forces withDistillers Company Limited (DCL). ‘The largest piece of capital formation that had ever taken place in the UK,’ in Morgan’s words. ‘The importance of these people to the economy is hard to exaggerate.’

In that year, Macdonald Greenlees – run by another forgotten knight, Sir James Calder – joined the new firm. Two years later, Mackie’s White Horse was absorbed (Sir Peter died in 1924).

The abiding mystery is why William Ross, the man who masterminded the Great Merger, was never honoured. Maybe he was too trade. Perhaps the heady days of whisky as the drink of celebrities had passed.

In one generation, the knights and Barons had transformed Scotch into a global spirit. We owe them a huge debt.

Thanks to Jacqui Seargeant, John Dewar Archive.

#546

Posted 04 March 2017 - 09:34

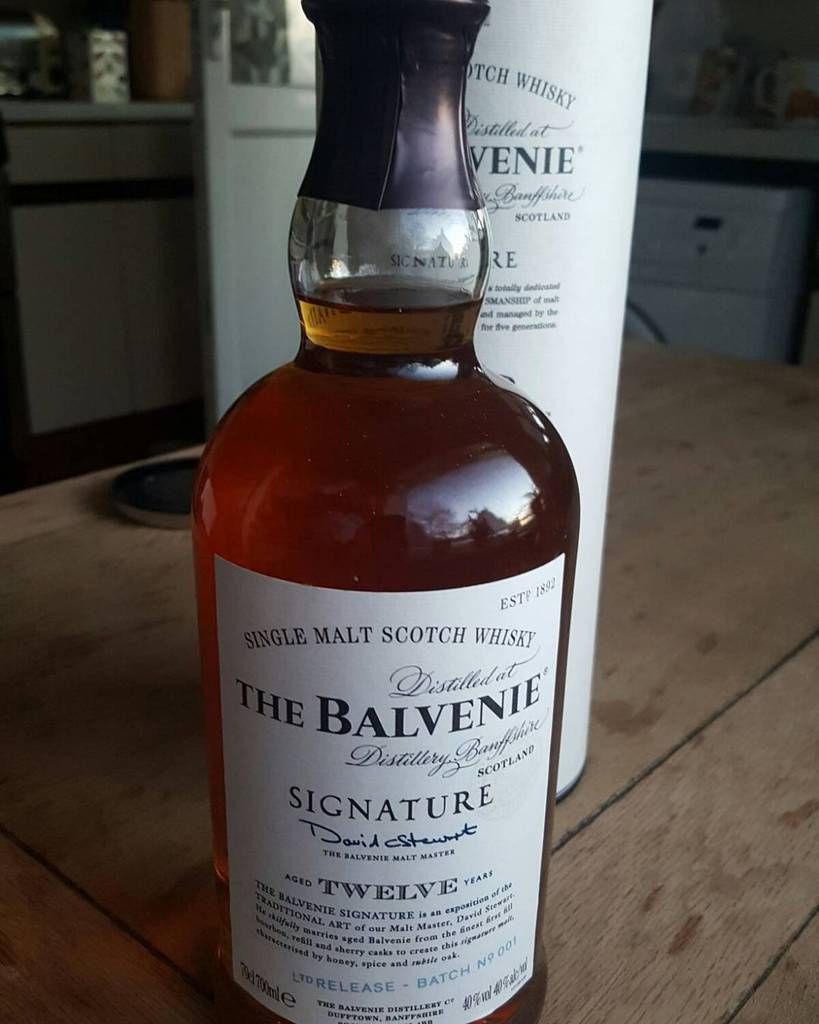

The Balvenie Signature 12yo batch #1

This 12 year old Balvenie was released in 2008 and was launched to replace the 10 year old Founders Reserve. This bottling was aged in first fill bourbon barrels and refill casks and sherry butts. This is from the first batch released!

Edited by Doorn, 04 March 2017 - 09:38.

#547

Posted 06 March 2017 - 15:31

WHY IS SCOTCH WHISKY BOTTLED AT 40% ABV? 04 January 2017 by The Whisky Professor

By law, Scotch whisky must be bottled at a minimum alcoholic strength of 40% abv – and yet other spirits, such as vodka and gin, can be as low as 37.5%. How come? As the Whisky Professor explains, the reasons have as much to do with wartime politics as anything else.

Test of strength: Whatever its abv at distillation, Scotch whisky must be bottled no lower than 40% (Photo: Glen Grant distillery)Dear Prof

Like much of the rest of humanity, with the dawn of another year I have been pondering ways in which to reduce my alcohol intake. Not for me the appalling ‘cold turkey’ of Dry January – I fear the shock to my system may do more harm than good – but I am taking a keen interest in the stated alcoholic strength on the labels in my drinks cabinet.

I notice that the (mercifully as yet untouched) supermarket own-label bottles of gin and vodka which entered my house as a festive donation from my dear Aunt Ethel have been bottled at 37.5% abv, and yet the corresponding bottle of ‘Glen McSporran’ finest blended Scotch clearly says 40%.

Upon further investigation, I have discovered that Scotch whisky must be bottled at a minimum strength of 40% by law. But why? I do hope that you can enlighten me.

Yours soberly

Mr D Tox

Dunboozin’

History lesson: The Prof’s answer on abv has more to do with politics than production

Dear Mr Tox

It is appropriate that I have been asked this question now, as the answer is 100 years old this year. As we’ll see, while there are quality issues behind keeping Scotch whisky at a minimum bottling strength of 40% abv, the main reason the figure was chosen – and eventually enshrined in law – had more to do with politics. This, therefore, is more of a history lesson than a technical one.

Let’s go back to 1915. The First World War had started and the whisky industry was coming under governmental pressure to Do Its Bit. In that year, David Lloyd George, the teetotal Chancellor of the Exchequer, created the Central Control Board (Liquor Traffic), whose powers included jurisdiction over sales of alcohol in ‘munitions areas’ – which comprised military bases and most of Britain’s main centres of population. Its remit also extended to advice on legislation which could help to curb liquor consumption. As I said, he was a teetotaler.

Lloyd George’s first attempt to introduce temperance by stealth was a proposal in his 1915 Budget to double the duty on spirits. He backed down after the whisky industry agreed to release its wares only after a minimum of three years’ maturation. This act of political horse-trading also helped, accidentally, to impose a degree of quality control.

He then tried another tack. In those days, most whisky was bottled at between 15 and 22 degrees under UK proof as it was then known (48.6-44.6% abv in today’s terms). In 1915, the Control Board permitted whisky to be sold at 35 degrees under proof (37.2% abv); the year after, Government gave the Board permission to ban production in all distilleries that weren’t licensed by the Ministry of Munitions, which was then run by… Lloyd George.

The same year, the Board also lobbied for distillers to further reduce the strength of their spirit sold in munitions areas to 50 degrees under proof (28.6% abv). Again the whisky industry protested and once again a compromise was reached, which standardised the strength of whisky everywhere in the UK at 42.9% abv (25 degrees under proof).

Temperance man: Lloyd George was concerned about the effects of alcohol on the war effort

The Board tried again and, on 1 February 1917, the Government (now headed by Lloyd George as Prime Minister) ruled that whisky had to be sold at no more than 30 degrees under proof (40% abv) and at no less than 50 degrees under proof in munition areas. A minimum price was also fixed by the Government.

The restrictions, bar price control, were lifted at the end of the war, but in 1920 duty was raised once again and whisky distillers were banned from passing the rise on. This increased financial burden meant it was impossible for them to bottle anything above 40% abv. The minimum strength had become standardised.

The fact that distillers bottled at a higher strength pre-war suggests that they understood that alcohol carries flavour and that, while cutting strength might have made them more money, it would also compromise quality.

The lower the strength goes, the greater the risk that you lose the more delicate (volatile) top notes. This is more clearly seen in gin and rum, where citric aromas virtually disappear when the bottling strength falls below 40% abv.

You can see evidence of this in whisky too by comparing the aromatic complexity of a whisky at 40% and 43%. The difference is marked. Forty percent might have been a compromise, but it helped to preserve whisky’s integrity.

Please do try comparing the bottles so generously given to you by Aunt Ethel and let me know the results of your tasting. No need to invite me to participate, though.

Yours aye

Prof

#548

Posted 07 March 2017 - 11:48

WHISKY OR WHISKEY: WHY THE TWO SPELLINGS?

Dear Whisky Professor,This question has been bugging me for a long time now, so I thought I’d just bite the bullet and ask you directly – why do the Scots spell whisky without an ‘e’, while Irish and Americans add it in?Is this because it’s made in a different way?Cheers,C WalterDear C Walter,Would that it were so simple. We are in the realm of tom-ay-to/tom-ah-to. The reasons between the spelling of ‘whisky’ and ‘whiskey’ are also somewhat confusing. So confusing – befuddling even – that by the end of this you may regret asking what seemed to be such a simple question.The spelling of Scotch whisky (no ‘e’) is enshrined in law. The same applies to Canadian whisky, while Japan, England, Wales, the Nordics, Australia (you get my drift) follow that lead. As you correctly point out, American and Irish producers use the alternate spelling, with the ‘e’. Mostly.These spellings were, however, only fixed in the 20th century. Up until then, the extra ‘e’ was being flung around as if at a rave in the 1990s. Some distillers – be they in Scotland, Ireland, or the US – used the ‘e’. Others didn’t.It is widely believed that during the 19th century, Ireland’s distillers began to use the ‘e’ as a way to differentiate their whiskeys from Scotch. They were becoming more popular and were regarded as being of higher quality. Having a different spelling gave the Irish another way of distinguishing between the two styles. Marketing, in other words.That said, the illuminating counterblast against grain whisky written by the main Irish producers in 1879 (which I recommend you read) was entitled Truths About Whisky (not whiskey), a spelling which was used throughout.To compound the confusion, while contemporary advertisements for Dublin whiskey merchants at the time show most spelling it with an ‘e’, distillers George Roe and Cruiskeen Lawn both did it without. The Cork brand, Paddy, only added the ‘e’ in the 1960s.Jack Daniel'sAmerican spelling: Why do some American whiskey brands like Jack Daniel’s spell ‘whiskey’ with an ‘e’ and not others?At least the Scots were consistent. Or so you might think. The ‘Truths’ blat was the first skirmish in a debate, which culminated in the Royal Commission sitting in 1908, entitled Enquiry into whiskey and other potable spirits. The ‘e’ spelling is used throughout.In his magisterial account Scotch: A Liquid History, Charles MacLean says that spellings became standardised soon after. The Irish stuck with the ‘e’; the Scots didn’t.You would expect things to be clearer on the other side of the pond. Canada maintained the ‘Scottish’ spelling (perhaps because of ties to the country), while America went down the ‘e’ route. This has been posited because of an influx of Irish distillers (or Irish whiskey). It could equally be another example of America’s individualistic approach to spelling but I do not wish to venture any further down that path.Not all American whiskeys use the ‘e’ however. Of the major brands, Maker’s Mark and George Dickel refrain from using the standard American spelling. In Maker’s case, this was as a tribute to the Samuels family’s Scots-Irish ancestors. Yes… I know.You may think that they are the exceptions to the rule, deviations from the legal norm. In fact, the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms (BATF) regulations, governing Bourbon etc, use the spelling ‘whisky’ as the correct legal term.Whiskey is permitted because it is traditional. The majority of distillers, you could argue, are exceptions and those such as Maker’s and Dickel are abiding by the law.Bet you’re glad you asked now, eh? I need a lie down and a whisky, or a whiskey.Prof

#549

Posted 08 March 2017 - 09:44

HOW DO SHERRY CASKS FLAVOUR WHISKY?

Sherry casks have been used to age Scotch whisky for well over 200 years. But what are distillers looking for when choosing casks, and how are they able to produce specific flavours? Does the type of wood also play a role?

Why Sherry?The Scots loved Sherry. The first record of it being drunk in Edinburgh was in 1548, but it was in the 18th century when it became a fashionable drink. By then, Sherry and rum Punches were the preferred drinks of the roistering members of Scottish clubs, which were the trend-setters of the period.There was also an element of patriotism involved, with many Scots either working for or owning Sherry houses: Arthur Gordon established Bodegas Gordon, then a distant relative William joined his uncle to found Duff-Gordon, while George Sandeman’s Port and Sherry interests were handled in Scotland by his relative Thomas from his base in Perth.In those days, Sherry would have been shipped to Glasgow and Leith in casks. This coincided with a dramatic expansion of the whisky industry. As there were no domestic forests in Scotland to use for casks, distillers turned to those being landed on the docks. These included rum and wine, as well as Sherry, but it was the latter that became the preferred option.What is Sherry?Sherry starts as a dry white wine made from the Palomino grape. This is then fortified and aged. The styles fall into two camps.The first contains fino, its subset manzanilla and amontillado. In these, the wine is lightly fortified and then placed in butts of 500-700 litres and aged in a complex system known as a solera.A thick, woolly blanket of yeast, known as flor, begins to grow on the surface of the liquid, protecting the wine from the air. As a result, the Sherry is pale in colour with a light crisp character, aromas of almond, chalk, green olive and, in manzanilla’s case, a distinctly salty tang.If this flor is allowed to die, then some oxidation takes place; the wine darkens in colour, and becomes an amontillado.The second camp contains oloroso and palo cortado. The same base wine is used, but this is fortified to a higher strength, thus killing any chance of flor growing (in the case of palo cortado, the yeast-killing process happens by chance, rather than by design). Ageing is in a solera and, because there is contact with air, the wines become darker and more nutty (walnuts), with some dried fruit elements.Pedro Ximénez (PX) – which is becoming increasingly used in Scotch maturation – is a separate style, made from the eponymous grape. After harvesting, the grapes are dried in the sun to concentrate the sugars and then fermented, fortified and aged. This naturally sweet wine with a huge raisined impact is used as a sweetening agent.What does a Sherry producer want from a cask?The butts used in the solera system are not made from active wood (they tend to be old American oak casks), so the wood has little impact on the Sherry. The taste of fino is caused by flor, the nuttiness of oloroso by oxidation and the sweetness of PX by the ‘raisining’ effect.What does a Scotch producer want from a cask?A distiller wants a cask to contribute flavour to the maturing whisky: vanilla, coconut, spice and chocolate from American oak; tannin, resin, clove and dried fruits from European oak.So, in Sherry wine production the flavours are driven by oxidation rather than by oak, while in the whisky maturation process, it is the other way around.On one hand, Sherry producers want a cask which has little impact, while the Scots want the opposite. Sherry producers use American oak for their casks, Scotch producers insist on European oak. There seem to be two different stories.How both sides are rightThe casks used for transporting Sherry were, however, different to those used to mature it. They would tend to be made from fresh wood (although fino would be transported in old casks so there was no wood influence) and would only be used for a few trips between Jerez and Scotland before being turned over to distillers. The result was that the Sherry casks used for whisky had power and flavour. While American oak was used, an increasing amount of European oak was used for shipping casks from the 1930s onwards.In the mid- to late 19th century, as whisky makers needed more casks, there was a decline in the volume of Sherry imported into Scotland. Blender William Phaup Lowrie (who was also the agent for González Byass Sherry) came up with a cunning solution. He imported new oak from America, coopered the casks in Glasgow and then treated them with Sherry before passing them on to distilleries. He too was trying to replicate the effect of a shipping cask.In 1986, all Sherry had to be bottled in the Jerez region, meaning that shipping casks ceased to exist. Distillers then began a programme similar to Lowrie’s. This time, though, they worked with cooperages in Jerez to make new casks to their specifications (air-dried European oak, seasoned with oloroso Sherry). Again, these are imitation shipping casks.What influence does the Sherry have on whisky?All of this might seem as if it is the oak which is the main driver in terms of flavour in Sherried whisky. That’s not quite true either. What happens during the seasoning process is that the Sherry modifies the flavour compounds in the oak.It is estimated that there is up to 10 litres of Sherry soaked into the wood of a Sherry butt. To see whether it was oak or Sherry that gave a ‘Sherried’ character to a Scotch, scientists simply added Sherry to Scotch to see whether the combination was the same as maturing in a Sherry butt. It wasn’t. Equally, ageing in an untreated European oak butt gave a different result.The ‘Sherried’ character, therefore, is down to the Sherry itself, but also oxidation and the way in which the Sherry has interacted with and changed compounds in the oak. All of these then interact over time with the maturing spirit.In very simple terms, there is more of an impact from the Sherry (or rather Sherry changed by oak and air) in the whisky’s youth, while in older examples you notice more of the oak (which is itself changed by the Sherry). This explains why a Sherry-finished whisky has more of a wine-driven character, when compared to a whisky matured exclusively in ex-Sherry casks.What these flavours are will also depend on a number of factors. A first-fill bespoke European oak ex-Sherry cask will have maximum impact of clove, resin, dried fruit and tannin. The same cask filled for a second time will have less of those compounds available for the whisky. You can find ex-Sherry casks which have been refilled so many times that the ‘Sherry’ element is virtually invisible.Some distillers – Dalmore is a notable example – prefer to use ex-solera casks, which will have low wood impact, but a higher contribution from the wine (and oxidation).Horses, as they say, for courses.

#550

Posted 08 March 2017 - 10:07

Trne, poceo sam se navikavati da procitam interesantan clanak o viskiju uz kafu kad dodjem na posao. Nadam se da ce se primiti kao serijal, mon-fri, a preko vikenda ne moras. ![]()

![]()

#551

Posted 08 March 2017 - 10:19

Jel se pojmovi "blended" i "single malt" odnose samo na škotski viski. Praštajte ako vam pitanje deluje glupo, ali u viski se ič ne razumem s obzirom da su pivo i domaćica šljivka moja pića ![]() .

.

Pre neki dan sam, iz čiste radoznalosti, u jednom dobro snabdevenom Hipermarketu malo gledao ponudu i gore navedene oznake nisam viđao ako je pisalo Kentaki ili Tenesi viski, ali je obavezno stajala uz škotski.( ruku na srce, stajalo je samo blended, single malt nisam video ![]() )

)

#552

Posted 08 March 2017 - 10:21

Trne, poceo sam se navikavati da procitam interesantan clanak o viskiju uz kafu kad dodjem na posao. Nadam se da ce se primiti kao serijal, mon-fri, a preko vikenda ne moras.

Preko vikenda praktijujemo teoriju.

Skoro sam pisao da mi u zadnje vrijeme sherry matured whisky nesto ne lezi. U pitanju je samo finish koji mi je kiseo. U clanku gore pise da sherry finished whisky ima taj vinski karakter i to je moguc razlog te kiselosti koja mi ne stima.

#553

Posted 08 March 2017 - 10:29

Jel se pojmovi "blended" i "single malt" odnose samo na škotski viski. Praštajte ako vam pitanje deluje glupo, ali u viski se ič ne razumem s obzirom da su pivo i domaćica šljivka moja pića

.

Pre neki dan sam, iz čiste radoznalosti, u jednom dobro snabdevenom Hipermarketu malo gledao ponudu i gore navedene oznake nisam viđao ako je pisalo Kentaki ili Tenesi viski, ali je obavezno stajala uz škotski.( ruku na srce, stajalo je samo blended, single malt nisam video

)

Blend ili single malt nema geografsko ogranicenje, ali zato ima scotch. Scotch whisky (blend ili single malt) moze samo da bude iz Skotske.

Edited by Doorn, 08 March 2017 - 10:30.

#554

Posted 08 March 2017 - 10:36

Preko vikenda praktijujemo teoriju.

Skoro sam pisao da mi u zadnje vrijeme sherry matured whisky nesto ne lezi. U pitanju je samo finish koji mi je kiseo. U clanku gore pise da sherry finished whisky ima taj vinski karakter i to je moguc razlog te kiselosti koja mi ne stima.

To ti je snowflake princeza sindrom. Drmni dva nazor, treci ce vec da legne k'o budali samar. ![]()

#555

Posted 08 March 2017 - 10:38

To ti je snowflake princeza sindrom. Drmni dva nazor, treci ce vec da legne k'o budali samar.

![]()

Aj pocecu sa #whiskywednesday ![]()