Klasika

#661

Posted 19 October 2017 - 16:50

#662

Posted 23 October 2017 - 16:26

Iconic IndyCar team owner Vollstedt passes away

Monday, 23 October 2017

By Robin Miller / Images by IMS Photo

For three decades he was a designer, builder, fabricator, dreamer, adventurer and racer to the core. He gave Jimmy Clark his final IndyCar ride, brought the first female driver to Indianapolis in 1976 with Janet Guthrie and helped Len Sutton, Billy Foster, Cale Yarborough and Tom Sneva start their careers.

But Rolla Vollstedt, who passed away Sunday at the age of 99, was the embodiment of why people use to spend all their time, money and effort inside the walls of Gasoline Alley every May.

Like A.J. Watson and Bill Finley, Vollstedt (pictured above with driver Arnie Knepper in 1968) was never blessed with big budgets but parlayed his work ethic and practicality into 15 starts at Indianapolis from 1964 to 1983.

"Rolla lived for the month of May," said Dick Simon, who spent seven years driving for Vollstedt while becoming partners and fast friends.

A World War II veteran wounded in Europe, the native of Portland, Oregon returned home and got hooked on racing. He built a track roadster and hired Sutton to drive and they terrorized tracks from L.A. to Seattle.

In 1963, Vollstedt built a rear-engine car and came to Indy with Sutton in '64 – where they qualified eighth and ran in the top 5 until a mechanical problem. It was the first rear-engine Offy to make the show and also the beginning of a long association with sponsor Bryant Heating & Cooling.

Sutton ran 12th in 1965 and then NASCAR star Yarborough put Rolla's car in the show in 1966 and 1967. Gordon Johncock, Arnie Knepper, John Cannon, George Follmer, Denny Zimmerman, Larry Dickson, Bob Harkey and Emerson Fittipaldi all wheeled a Vollstedt-prepared car at various times.

And although he never won an IndyCar race, the highlight of his life came at Riverside in 1967. On a whim Vollstedt decided to phone up Clark, who was coming to Riverside as a spectator, and offer him a seat in his year-old chassis.

The world champion agreed and promptly put in on the outside of Row 1 next to Dan Gurney – prompting the great Brock Yates to write: "Clark had driven that car faster than what was thought capable of a mortal man." He stalked his F1 friend and rival for 23 laps before snatching the lead – only to blow up the next time around. It was the great Scot's final race in the USA as he lost his life the following April at Hockenheim, Germany.

"Greatest day of my life," said Vollstedt back in 1980 when he was reminiscing about his life in racing. "I've never been so thrilled and so proud and Clark was just an amazing talent. He also thanked me for letting him drive and apologized for missing a shift, can you imagine that?"

Of course if was Guthrie (pictured above, with Vollstedt at left) that put Vollstedt on the media map forever when he chose her to drive his car in 1976. With zero open-wheel and high-speed experience, it was not a popular pick with the IndyCar establishment but the first female to run IMS handled the pressure and didn't put a wheel wrong all month despite not qualifying.

But Guthrie returned a year later and made history – qualifying Rolla's year-old Lightning in 26th place before dropping out early in the race with engine trouble. "Rolla was thorough, thoughtful, smart and passionate about the sport and will always have my admiration and respect," said Guthrie.

Rolla's last hurrah came in 1981 when Jerry Sneva hung it out and qualified Vollstedt's two-year-old model on the final day of time trials only to be disqualified for tampering with the pop-off valve. It was the height of the USAC/CART war and USAC was more than happy to look the other way for its lifetime member, only to have driver Steve Krisiloff rat out Vollstedt to officials.

As big money began to take over, Vollstedt was done competing by 1983.

#663

Posted 23 October 2017 - 19:37

To je čuvena Rote Sau (crvena krmača), bila je ovde izložena u salonu neko vreme, ali nisam stigao da je vidim.

#664

Posted 24 October 2017 - 03:00

To je čuvena Rote Sau (crvena krmača), bila je ovde izložena u salonu neko vreme, ali nisam stigao da je vidim.

Tacno tako - crvena krmaca, prvi AMG. Tacno 50 godina star!

#665

Posted 29 October 2017 - 16:55

‘An F1 driver was dangled from a car for spilling cocaine’: Exclusive extract from “The Mechanic”

F1 history

29th October 2017, 12:00

Author Keith Collantine

“The Mechanic” reveals what really happens in the heat of a Formula One garage from McLaren’s former number one mechanic Marc Priestley.

The book will be published on November 2nd but before it hits the shelves here is a exclusive excerpt for F1 Fanatic readers from the third chapter.

Paranoia and Playboys

Anarchy often ruled behind the scenes, despite the precision and quality of work taking place in the garages. I suspect McLaren would’ve loved a team of perfectly cloned, robotic mechanics and engineers that could meet the company’s unique and constant demands for attention to detail; a crew that represented the company in a polished corporate manner. What Ron Dennis had instead was a group that worked impeccably in the team colours, but once set free from the shackles of the racetrack, enjoyed the liberal, lavish behaviour that Formula One insiders thrived on at the time. I soon learned that working in F1 brought with it an often debauched and hedonistic lifestyle.

I’ve found myself in the back of a stretch limousine as drugs were passed around freely, even though the teams obviously had a total ban on drug use. On one occasion an F1 driver was dangled out of the window of a moving car for accidentally knocking over someone else’s line of cocaine. I visited parties where there was almost no attempt to conceal the class A drug-taking happening on the dance floor, and at others, high-class models and prostitutes were selected and paid for by teams to adorn their glamorous venues. I’ve heard of at least one F1 driver who was caught drink-driving in Monaco, but was let off because the officer who’d caught him was later very well ‘looked after’ at the next Grand Prix as a special guest, and the incident went undocumented.

There’ve been a long list of cover-ups and deliberately misleading stories over the years. I’m sure it’s even worse if you go back another generation of the sport, but F1 was a wild and fun place to be during my time. Luckily, I managed to stay out of serious trouble, but was never far away from a bit of fun and a joke. I covertly appeared in the back of almost every celebratory Ferrari team photo throughout 2006, by running over at the last moment as the team were assembling in the pitlane and jumping up in my McLaren kit. I even ended up on the back cover of Michael Schumacher’s biography, buried in amongst the red team shirts in one picture.

I jokingly threw a Bacardi and Coke into the face of a very drunk Schuey at a Mercedes celebration in Germany, and once rewired the horn into the brake pedal of our test driver Darren Turner’s road car while he was out on track. We’ve been thrown out of bars and nightclubs and had to send letters of apology, together with signed team caps and merchandise, in order to be allowed to remain in certain hotels after more destructive incidents. We just couldn’t help ourselves, but over time, I’ve managed to convince myself it was our way of letting our hair down and off-setting the high pressure, punishing hours and gruelling schedules during that era of Formula One. Whilst it’s not an excuse, it might at least serve as an explanation for some of our more questionable behaviour.

As a young man in F1, I partied hard. On more than one occasion I remember my phone’s morning wake-up alarm going off while I was still leaping around a dancefloor somewhere. We became skilled at sneaking back into hotels undetected, usually through side doors, while our elder, more responsible teammates unsuspectingly had breakfast a few metres away. After a super-quick shower and change, we were back downstairs and ready to return to work again. Tiredness and hangovers were something I managed to deal with in my younger days (I guess we all do) and it wasn’t uncommon to repeat the process night after night, something I couldn’t even dream of doing today. Despite playing as hard as we did, though, we always managed to find a way to focus on the job when it mattered.

Friday was normally a traditional night off from the booze, mostly because it was our longest day at the track. Having started around 7am, if we were finished in the garages by 11 to 11:30pm, it was deemed a pretty good day and it’d guarantee at least seven hours of much-needed sleep and recovery time after the previous few evenings of partying. That said, I remember a particularly horrific occasion in Brazil, after two near-sleepless nights out, when at around 11pm on Friday evening all we had left to do was push our car along the pitlane to the FIA garage and check its weights and measurements for legality – a mere formality. Imagine my horror when we wheeled the car onto the official precision flat plate, only to discover the measurements all pointed to some serious chassis damage. A significant crack was then uncovered beneath the driver’s seat area. I couldn’t believe it. I was exhausted, broken and already desperate for sleep. Back to the garage we went and the resulting chassis change meant I finally rolled into bed around 4am

Although I loved finally being part of the pitstop crew, I’d become desperate to move into a more permanent, active role than my occasional nose cone changes. Annoyingly, though, without someone actually leaving the team, key spots on the pitstop crew didn’t open up very often. Still, I got variety, working in a number of fringe positions, starting with holding open the sprung ‘dead man’s handle’ on the refuelling rig, which was a safety device to automatically shut off fuel flow in the case of an accident; I held the ‘splash board’, a long lollipop-type device, like a protective screen on a stick, which prevented the fuel nozzle from spraying potentially explosive fluid onto the hot exhausts and brakes at the rear; I steadied the car; I cleaned the radiator ducts; I adjusted the front wing; I topped up the engine’s pneumatic system. I did all sorts of things when needed at different times over my first year, but I was adamant I wanted to get myself into a more regular, more senior position as quickly as possible.

Eventually, at the end of the 2002 season somebody left the race team and I was moved onto the right rear corner crew, initially as ‘wheel-off man’, and I loved it. I was involved in every single pitstop from then on, taking off the right rear wheel and dumping it on the ground behind me, then quickly turning round to pull on the release handle of the refuelling nozzle, in order to assist the fuel man. It felt like an added responsibility, which fed my narcissistic tendencies for a while longer. I was in my element.

Refuelling was a major part of pitstops at that time and it was generally the procedure that determined the total length of most stops. Once all four wheels were changed, everyone would wait for the fuel nozzle to detach, before releasing the car back into the race. As such, it was a job we worked on improving wherever we could, and one of my favourite technical pitstop tricks was in this area. Once the nozzle was attached to the car, fuel would flow through the giant, aircraft specification hose at 12 litres per second. When the system had delivered the required amount of fuel, a motorised butterfly valve inside the nozzle would close, and once completely sealed, the lights on the display would change from red to green. That was our cue to pull back on the safety and release handles before detaching the nozzle. Every team had the same standard equipment and it was strictly forbidden to modify or adapt it in any way.

Some years earlier, the Benetton team had removed a fuel filter inside the nozzle to speed up the flow of fuel into the car. The theory might have been correct, but the most infamous pitstop fire in modern history, on Jos Verstappen’s Benetton car in the Hockenheim pitlane in Germany in 1994, meant they were rumbled. Even tighter restrictions and checks on the equipment were immediately implemented.

Realising there was nothing we could do to enhance the rig, we focused on the human factor instead. There was always a moment of delay between the required amount of fuel going into the car and the motorised shut-off valve fully closing. That delay was then increased by the mechanic’s reaction time in removing the nozzle from the car once the green light had flashed up. Our solution was ingenious: we rigged the fuel man with a stethoscope, which traversed up his sleeve and into a discrete earpiece. The other end (the bit the doctor normally presses to your chest) was pushed onto the fuel nozzle for each stop. The electric motor inside whirred into action when it was time to close the butterfly valve, and by listening in, the fuel man was able to react more quickly. He could start the process of pulling back on the release handles and by the time the valve was completely closed and the green light illuminated, the nozzle was almost detached. It might have only saved us a second or less with each stop, but those margins were sometimes the difference between us getting out ahead of, or behind, our main rivals. It was also technically legal, since we hadn’t modifed the standard fuel rig in any way, although we knew the FIA would have almost certainly frowned upon it, had they found out. We went to great lengths to keep the whole thing top secret.

I loved the technical arms race in Formula One, and pitstops had definitely become part of that game over the years. There was pride at stake, as much as it affected the race result, and people looked for any and every advantage. They were spending millions of pounds on technology in order to shave tenths of seconds off a lap time when the same, and much more, could often be achieved from within the pitlane. McLaren explored new ways to cover every possible eventuality and scenario, and whenever we found a potential advantage, it had to be shrouded in secrecy and kept away from the prying eyes of other teams for as long as possible.

“The Mechanic: The Secret World of the F1 Pit Lane” is published by Penguin Random House UK on November 2nd.

#666

Posted 29 October 2017 - 17:46

#668

Posted 31 October 2017 - 03:28

#669

Posted 02 November 2017 - 15:57

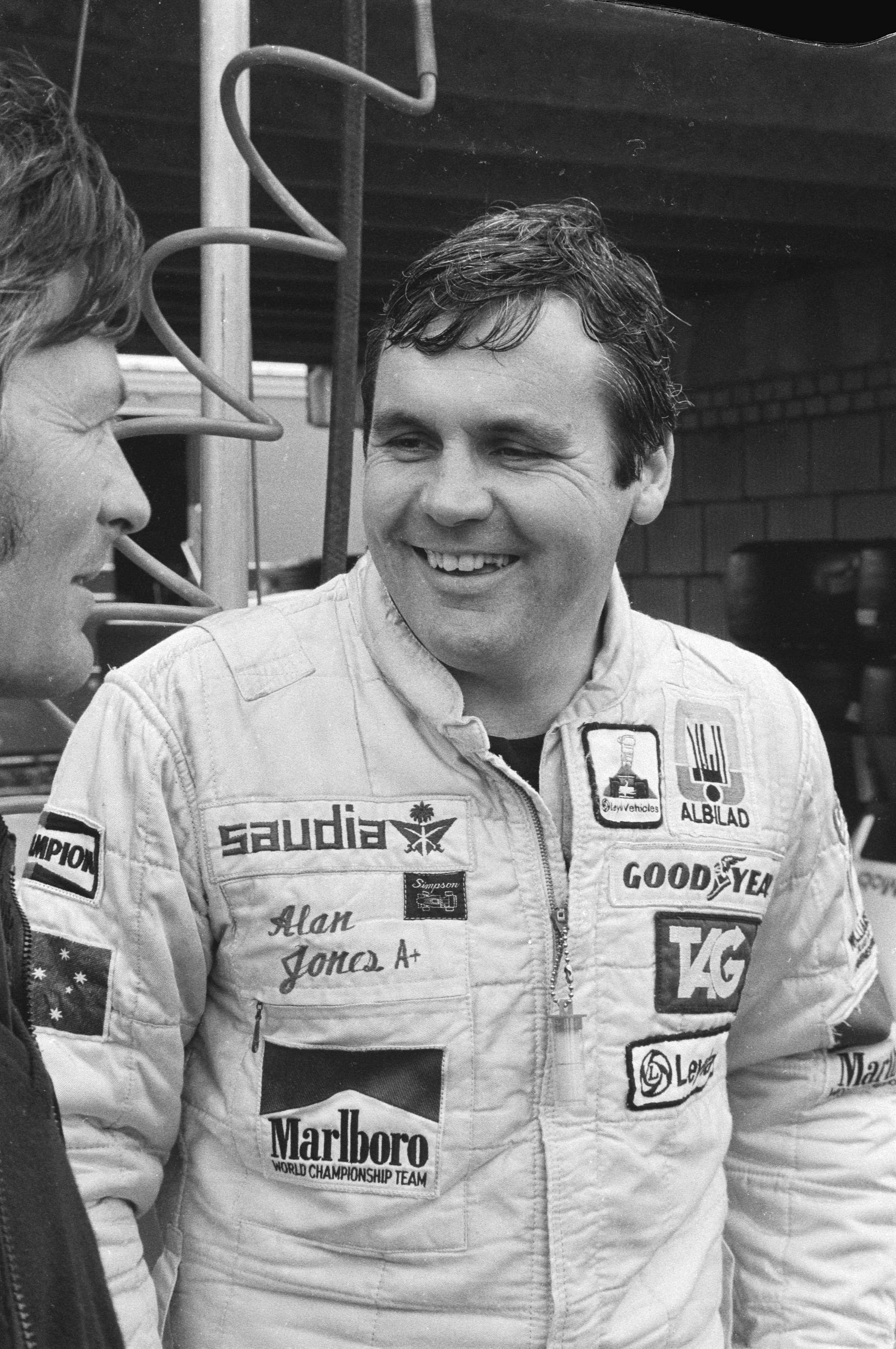

Srecan 71. rodjendan prvom Vilijamsovom sampionu Alenu Dzonsu!

#671

Posted 05 November 2017 - 18:31

Remembering Horst Kroll

Canadian auto racing legend passes away at 80.

By Norris McDonald

Sat., Nov. 4, 2017

I first met the late Canadian auto racing legend Horst Kroll in 1971 when my wife and I bought our first house, a bungalow, on Meadowvale Rd. in Scarborough just north of Lawrence.

The late Gunther Decker lived at the corner and kept his Formula Ford in the garage attached to his house; Horst had an automobile repair facility in the village of Highland Creek, just across the Kingston Rd. bridge, and stored his Formula Vee or Formula 5000 or Can-Am Frisbee — or whatever exotic machine he had at the time — in a trailerin a vacant lot next to it. I felt surrounded by racing cars and German racing drivers, and I was in Heaven.

I didn’t do business with him because I was a General Motors man at the time and his garage catered to Volkswagens, Porsches and other European brands. But one day, my young son, Cameron, although he wasn’t hurt, rode his tricycle into a wall in the house with such force that he bent the front wheel. I figured, ‘Why not?’ and took the trike over to Horst to see if he could fix it.

“It’s a first for me,” he said, looking at me, “but a wheel’s a wheel.” Whereupon he took out his cutting torch and used the heat to fix my kid’s tricycle. I think he charged me two bucks.

Horst, who died a week ago Thursday at 80, was remembered this week as a courageous, determined, brave, talented, unique, and totally original gentleman.

Courageous, because — when still a teenager — he left his friends and family behind and escaped from East Germany to eventually make his way to Canada, being unable to speak a word of English when he arrived.

Determined, because he originally went to work at Volkswagen Canada but soon struck out on his own, as mentioned, to create and operate that European automobile service and repair garage in the eastern Scarborough area of West Hill, out of which he ran his racing operations.

Brave, because he raced anything and everything in those early years, which was a dangerous time in auto racing. He started off in ice-racing and retired as a driver after winning the last Can-Am Challenge Cup championship in 1986. He was so proud that he once said to the late, great, world driving champion, John Surtees: “You were the first Can-Am champion and I was the last.”

(It was also said about his bravery that it took real guts in 1986 to turn over his second Can-Am entry to a young Paul Tracy, who behaved himself for once and won the very last Can-Am race ever held, at Mosport. Horst finished second, right behind the precocious teenager, who was known to be hard on equipment but kept his nose clean that day.)

Talented, because not only was Horst Kroll a great racing driver and team owner but he designed and built a brand of Formula Vee racing cars, called Altona Vees, that won national championships.

Unique, because not only did he race in Canada but he competed at the highest levels in the United States, where he was known and admired. In total, he won eight auto racing championships in his career, including the overall Canadian Driving Championship in 1968.

Totally original, because even in his retirement years, you knew Horst was around. Whether it was at the Molson/Honda Indy in Toronto or races at Canadian Tire Motorsport Park, he would zip around the pits and paddock areas aboard his homemade motorized scooter that he operated with the same abandonment that he’d driven his racing cars.

Retired Toronto Sun racing writer Dan Proudfoot, who was close to Horst in his later years, once quipped that Kroll was the only man he’d ever met who’d slept with the legendary Roger Penske.

Penske, who was running a Porsche at Harewood Acres, a long-gone airport racing circuit near Jarvis, west of Toronto, in the late-1950s, early-1960s, was driving himself at that time before becoming a team owner and industrialist.

Horst picked up the story in an interview with racing historian John Wright:

“They were changing an engine. I offered to help. The job was finished at 10 at night. Only Roger and I were left. He asked me where was I staying. I didn’t speak any English and he had to pantomime sleeping with his hands under his head and his head tilted to one side. I shrugged. He offered his motel room.

“Roger and I left in a station wagon. At the motel in Jarvis, not far from the track, Roger pulled the mattress off the bed and he slept on the floor. I slept on the bed.”

Horst Kroll, of course, was an early inductee to the Canadian Motorsport Hall of Fame and Chairman Hugh Scully had this reaction to the news of his death:

“I am saddened to learn of the passing of Horst Kroll. He was an energetic, dedicated and accomplished road racer who competed during much of his adult life.

“Horst was very personable, passionate about motor sport and always ready to help others. Over the years, we became friends.

“He certainly deserved his election as an honorary member of the Canadian Motorsport Hall of Fame for his contributions to motor sport in Canada. On behalf of the Hall of Fame, I express our condolences to the Kroll family.”

Here is a brief — and I mean brief — recap of Horst’s career, again thanks to historian Wright:

1963: He won the Class 9 Canadian Ice Racing Championship against Porsches, Corvettes, and twin cam MGAs. He also appeared in his first road races.

1964: He won the first of his three Formula Vee championships, this one in a Canadian built Huron Formula Vee, the second and third in a Kelly Vee.

1966: He competed at the Twelve Hours of Sebring, partnered with Jacques Duval and finished eighth overall, second in class.

1967: In a Kelly Porsche (a Lotus 23 Porsche-powered clone), he won the Under-2 litre Canadian Championship, and in 1968, won the Canadian Championship overall against the larger Can-Am style cars. In addition, he won the DAC (German Automobile Club) Gold Medal — complete with diamonds — as the club’s top international racer, and Porsche gave him their top award, presented by Ferdy Porsche himself.

1969: It was time to move up in the ranks, and so, with a new Lola T142, he competed in the Gulf Canada Series for Formula A cars and in the U.S. Continental Series. In that same year, he started construction of his Altona Formula Vees, finishing third in the Canadian Formula Vee Championship with an Altona prototype.

1970 to 1976: Horst was a consistent top 10 finisher in the Formula A Continental Series.

1977: The Can-Am series was revived for centre-seat, closed-wheel racing cars, and Horst converted his Lola T300 to a Hayman-Kroll Racing Lola. He finished third in the opener at St. Jovite and ran seventh overall in the series.

1978 to 1982: Horst continued to race on a very limited budget but consistently achieved high placings in the series, usually finishing in the top half of the field. In 1983, he finished fifth in the series and was third in 1984.

Things were looking better in 1985 when he won the Canadian Championship for the third time, based on his competition record in international events. Overall, that success was matched with a third overall placing in the Can-Am series that year.

1986: His last year of competition, he won that last Can-Am championship and owned the car that won the final race with young Tracy aboard. He was inducted into the Canadian Motorsport Hall of Fame in 1994.

Now, I have two favourite Horst Kroll stories. The first was when he — with help — sold a sponsorship to Silverwood Dairies for $10,000 to represent their Chipwich ice cream sandwich. In negotiations, he mentioned that the Chipwich Charger (as it would be known) would be a Galles GR3 Frisbee sports racing car. The only problem was that he didn’t own the car. He had a line on it through another Canadian racing champion, Eppie Wietzes, but the deal hadn’t been done.

In the end, he spent the $10,000 to close the deal on the race car, but then — as was often the case — had to try to run the season on literally next to no money.

Which was really what Horst Kroll was all about. In conversation this week, Myles Brandt, president of Canadian Tire Motorsport Park (formerly Mosport), who has been at the helm of that place forever, said he always enjoyed running into Horst “because he was a character.”

“He always showed up,” Brandt said. “Sponsor or no sponsor, he always put on a good show for the fans.”

My second favourite story is about the old Sundown Grand Prix, which has been an on-again, off-again race — mostly off these days — that started at Harewood Acres before Mosport was built. (An aside: driver Penske won the first two, the first co-driving with Harry Blanchard, the second with Peter Ryan, both Canadians.)

As I wrote in a Toronto Star Wheels column a few years ago, two drivers were frequently in contention to win the Sundown but always (it seemed) finished second or third. Klaus and Harry Bytzek always gave it the old college try but just couldn’t make it all the way to the top.

So, it’s 1975, which turned out to be the second-last Sundown Grand Prix before it went “off,” and the sort of things that happen to make motor racing stories great happened.

Klaus Bytzek, for one reason or another, wasn’t able to make the race. As a result, his brother, Harry, had pretty much decided not to enter. Then he got a call from his buddy, Jacques Bienvenue, who also didn’t have a partner. Both those guys owned Porsche 911 RSRs.

Bienvenue and Harry Bytzek decided it would be a scream if they entered the race as each other’s co-driver. The plan was that each would start the race in his own car and then they’d switch halfway through and finish in the other’s.

“So, I took the car out to Mosport,” Bytzek told me in an interview. “But when the organizers found out what we had in mind, they said to us, ‘You’ve got to be kidding!’ So, they wouldn’t let us do it.”

By this time, though, Harry had the bit in his teeth and wanted to go racing. But he needed a co-driver. He looked around the paddock and who should come walking along but his old pal, Horst Kroll.

“Ask Horst what happened,” Harry said to me, so I did.

“I had a free weekend,” Horst continued. “There was nothing going on in Formula 5000 (the series where he was racing at the time), and I was just looking to have a relaxing couple of days off. I had a girlfriend and we’d been out on the Friday night and I was feeling a little rough. Saturday comes and she said, ‘Let’s go out to Mosport.’ I didn’t want to argue, so we went.

“When we got there, I heard that Harry was looking for a driver. I was avoiding him like crazy, but my girlfriend made sure we bumped into each other. I told him I didn’t have my helmet or my driver’s suit so I couldn’t race. My girlfriend said, ‘I’ll go get them,’ so she went flying back to Toronto to get my stuff, and before I knew it, Harry had a co-driver.

“The funny thing is, I didn’t even know where fifth gear was on the RSR. I found it, obviously. I had a pretty good weekend, too. I didn’t make any mistakes. And you know what? We won the Sundown Grand Prix.”

Over the years, Horst won a lot of races. And he did it because of desire. Writer Proudfoot, who is travelling and was unable to attend services for his buddy, sent me a note:

“He was the last Can-Am champ before the SCCA shut it down,” Dan wrote. “Horst was pretty much the last man standing: Danny Sullivan and Al Unser Jr. had moved on to IndyCar, Patrick Tambay, Alan Jones and Keke Rosberg would be remembered for Formula One exploits.

“But say this for Horst Kroll: He was a top-10 racer even against the big dogs. Tenacity fuelled his rise, not cash. At the Mid-Ohio track, I remember making the rounds, circa-1983, as he checked the fully funded teams’ garbage bins. They threw out gears and other expensive parts after a prescribed number of racing hours. Horst knew they had plenty of miles in them before they failed.

“His daughter, Birgit, excitedly pointed out that Paul Newman was barbecuing burgers next door to their modest motor home. Horst didn’t know who Newman was. When told, he said he never went to the movies.

“My subsequent story in The Sunday Sun was titled ‘Team Poverty.’ Yet, he prospered, after a fashion, with major sponsorship one year — his car became the Chipwich Charger promoting a new ice cream treat — and fielding extra cars for paying drivers. Paul Tracy won his first major race driving a Kroll car, beating Kroll in the process.

“To the end, Horst handed out his business card to everyone he met. ‘Can-Am Champion,’ it said, and that’s exactly how Canadian racing fans will remember him.”

Retired Star sportswriter Frank Orr, who covered the auto racing beat (plus a little hockey) for years, credits Horst with educating him about auto racing:

Describing Horst’s race car preparation as immaculate after writing about him winning the Canadian Driving Championship in 1968, Orr sought out Kroll’s Altona Motors (the shop in Highland Creek) when his 356B needed an engine job.

Said Orr: “Done. In the process, Horst also lightened the flywheel to make it faster-revving. And, incidentally, my racing education began as we became friends.”

Scott Goodyear is a retired Canadian racing star, Indy 500 veteran and now colour analyst on ABC television’s coverage of IndyCar racing. He sent this note when he heard:

Horst was “one of the true, hard-core racers who worked on his car during the week, put it on the trailer and towed it to the track and went racing on the weekend,” Goodyear wrote. “He was a very special breed of driver who did it all himself.

“I first remember Horst when I started racing at Mosport as he was driving Cam-Am cars — the monster cars of that era. I would watch him pilot his Frisbee around the track, being amazed at his speed. He was one of the Canadian heroes to young drivers like me along with Eppie Wietzes and Ludwig Heimrath Sr.

“I remember when Horst showed up with Chipwich as a sponsor on the side of his car. It was a signal to the young drivers that you could sell racing sponsorship in Canada.

“Always approachable, he loved talking about any type of racing. We’ve lost one of the original gentlemen racers.”

Another Scott, Scott Maxwell, who went on from Mosport to win his class in the 24 Hours of Le Mans, also has fond recollections.

“My overriding memories of Horst are from when I was a young kid watching up at Mosport in the ’70s,” Maxwell said. “His cars stood out because they were always bright yellow. It didn’t matter if it was his Can-Am car or Formula 5000 or even his Formula Vee, they all looked the same.

“And just like the other top drivers of that era, his number was iconic. Eppie (Wietzes) was No. 94; Mo Carter was No. 88 and Horst was always No. 37. Horst never had the best equipment and probably always raced pretty much on a shoestring budget. But if you think of those grids and the stars that drove in those races — Andretti, Hulme, Revson, Redmond, Weitzes — what a great era.

“In hindsight, it’s pretty impressive what he did out of his own garage.”

Maxwell said that Kroll was always very supportive of his early racing career.

“I think I raced against him a couple of times in Formula Vee when I was just starting out in the mid ’80s. But what I do recall is he was really keen for me to drive his Can-Am car, and of course, I was either too dumb or naïve to think this might be a bad idea. I didn’t have any budget anyway, and I drove for Brian Stewart then, and I think he basically told me no way. Brian was very protective of me. That was the year I think that Paul Tracy and I were battling it out for the Formula Ford championship and we were really hard on each other — lots of contact and a big rivalry so we weren’t exactly best buddies.

“Of course, I didn’t realize that Horst was making the same offer to Paul. I think Horst and Tony (Tracy, Paul’s father) were tight and Horst was out there trying to make the best deal he could! In the end, Tony and Horst did the deal and of course Paul went out and dominated the Can-Am race. I was envious at the time; I missed my only chance to drive in a Can-Am. But Horst made the right decision and Paul delivered.”

Paul Ferris, author of a book on Paul Tracy, Never Too Fast, pitched in with this:

“The main thing that sticks in my mind about Horst was that he was honest, very generous with his time and more than happy to talk about racing.

“I approached him for an interview out of the blue for the Paul Tracy book. We had never met or crossed paths before and yet he agreed to talk right away. He answered all my questions (and my followup questions) and pointed me to other people who could help. His honesty was probably most helpful. He was never malicious but there was no PR filter about what he said.

“For someone like me who had taken on this book project and quickly realized how much work was in front of me, it was great to have someone like Horst make himself available and help me set the foundation for a lot of the interviews that were to come.”

OK, it’s time for a moment of levity.

As everybody who knew Horst knows, he was “follically challenged.” He started losing his hair at a young age and, like many men, tried to disguise the fact as he got older. So, we get this little gem from the Star’s own Jim Kenzie:

“When we were running the 24 Hour race at Mosport in the SAAB 9000 under the auspices of World of Wheels magazine (there were several 24-hour events at CTMP in the 1980s and ’90s). Horst was our designated ringer. We were putting in time between driving stints at Lynn Helpard’s place near the track. We were taking a swim in the pool and Horst dove in. He surfaced here — and his hairpiece surfaced over there.”

Ed Moody, recording secretary and banquet chef for Corner 2 Racing, an unorganized organization of racing fans who gather at the top of the hill overlooking corners one, two and three at Canadian Tire Motorsport Park every race weekend, watched and admired Horst for many years.

“Horst always had the time to talk,” Mr. Ed said. “I took my 6-year-old daughter to the final Can-Am race at Mosport. Thanks to Horst, she got to see Horst win the championship and Paul Tracy win the last Can-Am race. After that, I began taking her to the Molson Indy, and Horst would be buzzing around on a motorized skateboard and always had the time to stop and have a talk.

“Even when he quit racing, he seemed to enjoy being recognized for all he had achieved on a shoestring budget. And it really was a shoestring budget. I remember Horst doing some demonstration laps in the Frisbee a few years ago and he ran out of gas.”

Jonathan Brett has fond memories.

“In 1986, Horst gave me my first job out of college. It was only a one-month deal, I was tasked to find sponsorship for the 1986 Can-Am season. He placed me at an ad agency in Toronto where I used their facilities to write letters and contact prospective sponsors.

“We ended up getting the City of Scarborough to sponsor the Lola/Frisbee. I enjoyed hanging out with Horst at his garage and doing a bit of help around the shop and on the race car. He also had a sponsorship with SKF Bearings. I ended up getting a position with SKF afterwards, which was a direct result of Horst putting in a word for me.

“We ended up at his apartment a few times, having a few beers and talking about racing. He had an impressive wall of trophies. They were very enjoyable moments.

“After starting a family and moving to London, Ont., I got involved with vintage racing. I saw Horst at the track one more time when he brought the Lola/Frisbee for some laps at a VARAC vintage festival. He still had the touch with the car.”

As mentioned, Horst would keep a race car, or cars, in a trailer that he left parked on a vacant lot next to his repair shop in Highland Creek village. That trailer sat there for years — until one night, when somebody just went and hooked it up and hauled it away. The police found it fairly quickly and everything was intact (the thief, or thieves, probably did a double-take when they found out what they’d stolen) but Horst came to realize that maybe a vacant lot wasn’t a great place to leave such precious cargo.

Enter Fran Matsumoto, who’s owned a farm in the Uxbridge area for years.

“I first met Horst in the ’70s. It was at Mosport at some Can-Am race. I had been to a couple of races before, but I had never been in the paddock area and ‘behind the scenes.’ I was dating Horst’s friend at the time and he and Horst went off to talk and I was left with the car.

“I tried to stay out of the way of the two guys he had with him who were preparing the car, but I remember that they were very kind and would answer questions. I was intrigued.

“Horst came out to the car and suggested that I could have the privilege of polishing the car. I must have given him ‘a look,’ as he never asked me again.

“I never saw the Can-Am car again until he brought it up to the farm to store it ‘temporarily’ in the barn. For some reason, he could no longer keep it at his shop. I think he mentioned some sort of zoning problem. I did not ask. It was just here when I got home and did not leave until several years later when he took part in a vintage race in Mosport.

“Over the many years, Horst remained a good friend. He would come to the farm for dinner with bags of food for my dogs. He was very loyal and trusting (sometimes too trusting.) He was the kind of friend that you knew that you could be thousands of kilometres away and if you needed help, he would be there.”

Fran’s partner, Ralph Luciw, added:

“We called him every few weeks to say hello and, in my last call just a few weeks ago, he sounded good and said he was OK and that he was still swimming a couple of times a week.

“He was a wonderful character, and we’ll miss seeing him roll into the paddock with that old telephone truck hauling that beat-up old trailer that had long since reached its ‘best before’ date.”

The last word will go to Paul Cooke, vice-president, ASN-FIA Canada, which is the sport’s governing body in this country. Mr. Cooke sent me this statement:

“In 1994, Horst Kroll was inducted into the Canadian Motorsport Hall of Fame, Canada’s highest form of recognition.

“As one who shared the track and the sport with Horst, I had a consistent fondness for a genuine person with extraordinary mechanical skills, technical creativity, performance on the track and the ability to attract sponsorship for his passion, culminating in his success.

“Always ready to ask for help, always ready to help others, Horst carved an enviable reputation in Canadian and North American motorsport. Rest in peace.”

Horst leaves wife, Hildegard, and daughter, Birgit, as well as sisters Renate Streubel and Krista Silbersack. He was the son of the late Emile Kroll and Elisabeth Jany and uncle to Petr, Guido, Stefan and Holk.

He will be missed.

#672

Posted 07 November 2017 - 17:42

Bob Kinser 1931-2017

Sunday, 05 November 2017

By Robin Miller / John Mahoney

He was a mountain of a man, a barrel-chested brick layer from southern Indiana's stone quarry country who developed a talent, a temper and a following for sprint car racing that set the pilot light for his son's meteoric rise.

But Bob Kinser was hell on wheels long before Steve Kinser ever ascended.

Kinser, the patriarch of this famous open wheel racing family, passed away Saturday at the age of 86, and while he never ran Indianapolis or Daytona and didn't like to stray too far from Heltonville, he was a household name in short track racing for five decades.

It's estimated big Bob won over 400 features at Paragon, Bloomington, Kokomo, Haubstadt, Putnamville and Lawrenceburg in jalopies, bombers, late models and non-wing sprinters in addition to scoring a USAC sprint win when he was 54. He was inducted into the National Sprint Car Hall of Fame in 1999.

The late Jim McQueen, one of sprint car racing's best minds and tuners, once was asked about the best dirt sprint racer he'd encountered prior to the beginning of the World of Outlaws in 1978.

"It's either Bob Kinser or Bubby Jones," McQueen replied. "They win everything."

Kinser was a weekend warrior because of his 9-to-5 job and four kids at home, but his battles with Dick Gaines, Bobby Black, Calvin Gilstrap, Cecil Beavers and Butch Wilkerson all over Indiana became legendary in the '60s and '70s. He drove for Karl Kinser, Dizz Wilson and Galen Fox, and Jones was happy to learn from the master.

"Bob was already a big deal when I came along and he was a helluva driver," said Jones, a standout in USAC and CRA from Danville, Ill. who made it all the way to the Indianapolis 500 starting lineup in 1977.

"He was always nice to me and a good guy, but of course I was also smart enough not to piss him off."

Bob Kinser (center) with sons Steve and Randy in 1975.

Prior to launching his WoO legacy and becoming the most prolific winner in sprint car history, Steve Kinser was asked to tell his high school classmates something about his father. "He likes to drink beer, race cars and fight," said the King.

Nobody can document whether Bob ever lost a fight, but he scored several TKOs after races and his trademark was a stubby cigar, an old fishin' hat and his red bandana. If he was provoked, the cigar would hit the ground – but not before the guy he just punched.

#673

Posted 10 November 2017 - 06:21

#674

Posted 15 November 2017 - 13:51

PRUETT: The Hitchhikers Guide to Motor Racing

Tuesday, 14 November 2017

By Marshall Pruett / Images by Glenn Dunbar/LAT & IMSA

"It was just something you did," said former Ferrari Formula 1 driver Stefan Johansson. "You didn't really think about it."

The Swede, like many of his contemporaries in the 1980s, made a habit of catching post-race rides back to the pits while holding onto the roll bar of a grand prix car. The haphazard era, when F1 became a live television product throughout the world, turned some of the sport's most famous names into hitchhikers thanks to two circumstances.

"Those f***ing engines made like 1500 horsepower, and they banned refueling from Formula 1, so guys were always running out of fuel on the last lap if they did a s***ty job of conserving during the race," Johansson admits.

"I mean, you're trying to race Ayrton Senna or Nigel Mansell, and they also want you to take it easy on the throttle pedal. I can say, at least for my defense, I wasn't the only one who had to pull off and park sometimes..."

Johansson's throwback video from the 1986 Mexican Grand Prix could be the most impressive of all with three drivers piled onto Nelson Piquet's Williams-Honda. With Johansson in his red Ferrari overalls perched on the right sidepod, Ligier's Rene Arnoux on the left sidepod, and Arnoux's teammate Philippe Alliot straddling the engine cover like he was riding a horse, Piquet turned his FW11 chassis into the world's most expensive Uber.

"That one was crazy, man," Johansson recalls. "Normally it's one guy, but never three. I think it was a record!"

Surprisingly, sitting on top of sidepods carrying large radiators that struggled to keep the glowing 1.5-liter turbo engines cool was not a painful experience.

"You might think it would burn your ass, but it didn't," he said. "I don't know why, but it didn't."

Possibly the most famous hitchhiking footage came from 1991 when another Williams chassis, the FW14 Mansell drove to victory at the British GP, was used to gather an out-of-fuel Senna.

Between Piquet and Mansell, the ride-giving was taken to new heights in 1988 by the Electramotive IMSA GTP team. With its win on the streets of West Palm Beach in Florida by Geoff Brabham and John Morton, an unprecedented form of celebration was established when the crew of the No. 83 Nissan GTP ZX-Turbo climbed atop the prototype's expansive bodywork and toured the circuit with the checkered flag in hand.

With approximately a dozen people along for the cruise, it made for an unforgettable image that soon turned into a national newspaper placed by the Japanese brand."

I still have that original photo," said Kas Kastner, who turned Nissan into a four-time GTP champion. "When I saw that picture, I told our PR guy, E.C. Mueller, to go buy it."

Decades later, the hitchhiking is a rarity – an illegal act, in some rulebooks. Still, we receive the occasional surprise, like this year's Malaysian Grand Prix.

Sebastian Vettel conjured visions of the 1980s when he caught a ride with Sauber's Pascal Wehrlein after his Ferrari and yet another Williams – the FW40 of Lance Stroll –was involved in a situation that required another cool-down lap pickup.

For all of the money and effort that goes into making motor racing a perfectly polished affair, sometimes it's the unplanned moments, the most relatable ones, that bring big smiles. Need a ride? Sure, hang onto my zillion-dollar machine and I'll get you there.

#675

Posted 17 November 2017 - 04:47

Pregled sezone 1987 na zvanicnom Indikar kanalu donosi nam dva apsolutna klasika: