Hulk ima spektakularne rezultate u svemu u cega je seo osim u F1. Ne samo tokom napredovanja kroz nize kategorije, seti se da je pre neku godinu uz'o i Leman iz prvog pokusaja, imam utisak da bi i da dodje na Indi 500 odmah uzeo (a Alonso momentalno izvrsio samoubistvo ![]() ). Ono istina, nikada u F1 nije imao "alat" za vrhunska dela ali i sa ovim sto je do sada imao na raspolaganju drugi su se penjali na podijume, on ni da pipne. Vidi se iz aviona da tu ima kvaliteta za velika dela, ali nesto negde ne stima. Nece biti ni prvi ni poslednji kome je F1 karijera zestoko podbacila - vidi na primer pod Zan Alezi, od koga se ocekivalo u najmanju ruku da ce da bude novi Sena a on uz'o jednu pobedu u celoj karijeri...

). Ono istina, nikada u F1 nije imao "alat" za vrhunska dela ali i sa ovim sto je do sada imao na raspolaganju drugi su se penjali na podijume, on ni da pipne. Vidi se iz aviona da tu ima kvaliteta za velika dela, ali nesto negde ne stima. Nece biti ni prvi ni poslednji kome je F1 karijera zestoko podbacila - vidi na primer pod Zan Alezi, od koga se ocekivalo u najmanju ruku da ce da bude novi Sena a on uz'o jednu pobedu u celoj karijeri...

Klasika

#646

Posted 09 September 2017 - 13:33

#647

Posted 09 September 2017 - 16:00

Kad se setim Alezijeve kamere kako otpada i ostecuje i njegov i Bergerov bolid dok su bili 1. i 2. u Monci...

#648

Posted 16 September 2017 - 19:40

Apsolutni klasik na najbrzoj stazi na svetu, totalna dominacija Marija Antretija u prvoj fazi trke da bi ponovo postao zrtva "Andretijeve kletve" kao i na Indiju te iste godine gde je zbog kvara pobedu prepustio Alu Anseru starijem. Lider na tabeli sampionata Bobi Rehol je imao problema sa pitstopovima na pocetku trke zbog cega je izgubio nekoliko krugova, ali je sjajnom voznjom uspeo to da vrati i da se umesa u veliku borbu u finisu trke izmedju (ponovo) Ala Ansera i mladjahnog Majkla Andretija na kome je ostalo da cuva cast familije...

#649

Posted 17 September 2017 - 22:31

Bobby Rahal is reunited with three Ralt RT-1 Formula Atlantic cars he drove in the 1970s while visiting Sonoma Raceway for the 2017 IndyCar season finale, and reveals the time he was arrested before an Atlantic race in Canada...

#650

Posted 20 September 2017 - 16:51

Od danas je 42 godine mlad. Srecan rodjendan!

#651

Posted 20 September 2017 - 19:17

Sa druge strane, ljudi nisu automati, ovakav lik nedostaje današnjoj F1.

#652

Posted 25 September 2017 - 17:18

#653

Posted 26 September 2017 - 20:48

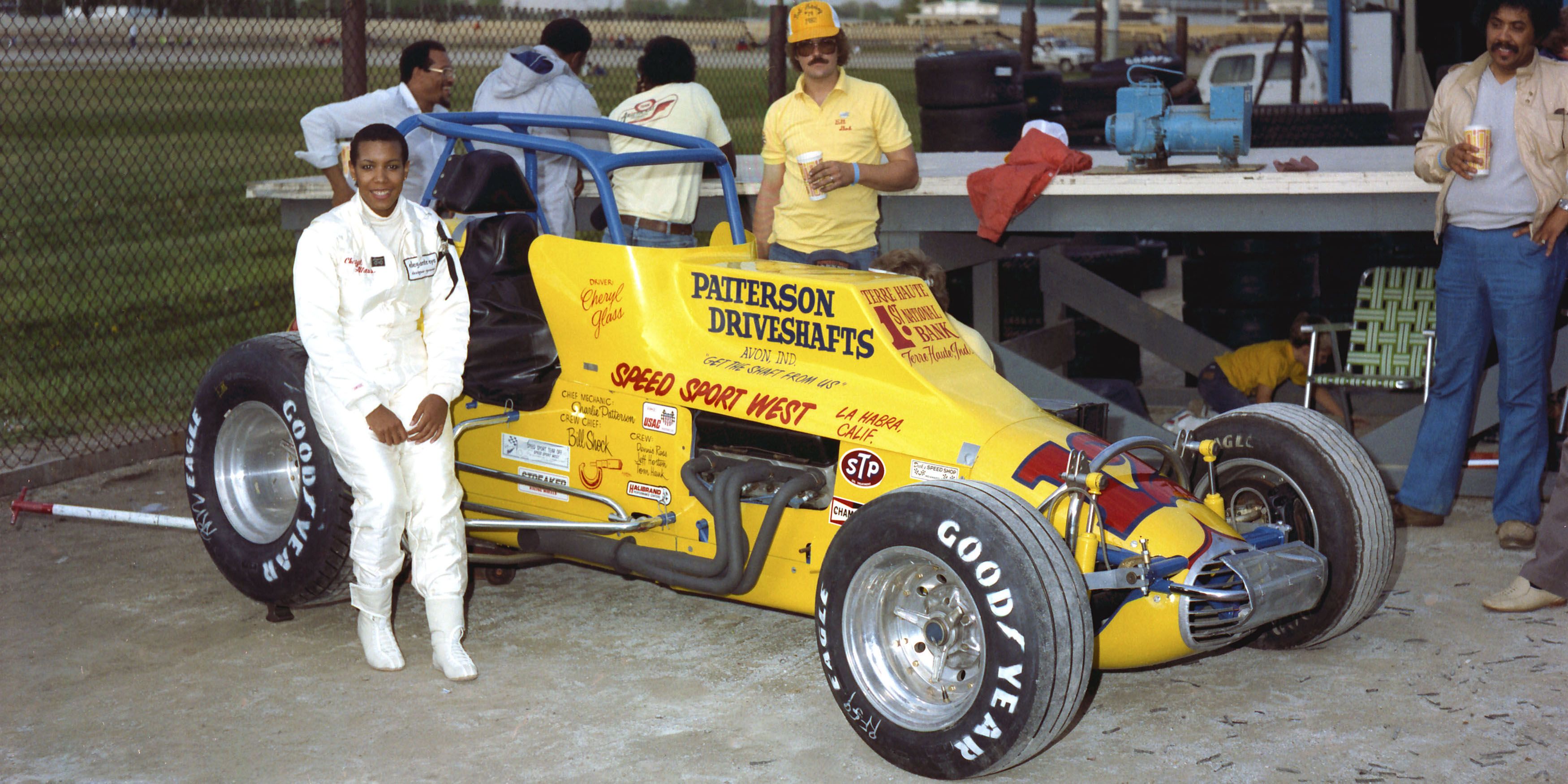

The Life and Death of Cheryl Glass

The female, African-American sprint car driver had Indy 500 ambitions, but why did the promising racer’s dream turn to tragedy?

By Marshall Pruett

Jul 14, 2017

The coroner listed her cause of death as drowning. Detectives from the Seattle police department ruled her death a suicide, the result of jumping off the Aurora Bridge into Lake Union.

Her family disputes any notion she chose to go over the edge, willfully plummeting 167 feet into the water below. No suicide note was found at the scene.

Why, 20 years ago on July 15, 1997, did the life of race car driver Cheryl Glass come to an end? Was the pioneering sprint car and Indy Lights driver a victim of foul play? Or, did the acts and circumstances that marred her final years somehow lead to the time-stopping outcome that summer day in Washington State?

These are lingering, frustrating questions that lack definitive answers.

Born in 1961 to Marvin and Shirley Glass in the San Francisco Bay Area town of Mountain View, the Glass family relocated to the Pacific Northwest in 1963. Cheryl’s parents, executives in the aerospace and telecommunications industries, raised a child prodigy.

As a scholar and young businesswoman, Glass was recognized for her intelligence and ambition. Thanks to her father’s passion for motorsports, race car driving was soon added to a mounting list of achievements. At nine, her career began with quarter-midgets and continued into half-midgets until she was 18. On the regional level, with Washington’s Skagit Raceway serving as her personal training ground, Glass developed into a serious short-oval competitor and regular winner.

The old third-mile bullring, responsible for producing Spokane’s 1983 Indy 500 winner Tom Sneva, and other little haunts–mostly of the paved variety–helped Glass hone her skills. Still in her teens, she’d fill a room with trophies and forge a reputation as a star on the rise. A woman, an African-American woman, was doing big things on the west coast motor racing trail in an era where a driver of her gender and color was singular.

Today, she’d earn some degree of notoriety for being a woman of color in a sport filled with men. But when she got her start, in the 1970s, and then in the 1980s where she took on bigger, faster sprint cars, and again in the early 1990s when she pursued her Indy 500 dreams by training in the Indy Lights series, Glass was one of one.

It also meant that as the black woman in her field, she attracted interest—of the positive and negative kind—for reasons that fell along rather predictable lines.

For those who held racist views, or felt women didn’t belong in a race car, Glass was an abomination.

"Women aren't supposed to be sprint drivers and most men (back in the Northwest) haven't really liked me," she said in an interview with the Indianapolis Star. "Their attitudes have made it very difficult for me to race. But I've been accepted around professional drivers. I was brought up to be very open-minded and I've never looked at it as 'I was black and couldn't do it.' I'm determined to prove I can handle it."

For those who were drawn to her skill, beauty, or the core item—the unexpected presence a black woman racing and winning in a testosterone-fueled sport, the stories came easily. They tended to strike upon all three keys.

A breakout name in Washington, Glass ventured to the Southwest in 1980 for a run in non-winged sprint cars at Arizona’s Manzanita Raceway. Strapped into the hellacious 410 cu. in. V8-powered tubeframe machine, she’d compete on dirt against future two-time Indy 500 champion Al Unser Jr, among others, around the short oval.

“I didn’t know her that well, but she was a good driver,” Unser told RoadandTrack.com “She was an abnormality at that time. A female driving sprint cars wasn’t considered normal then. Shoot, it still isn’t something you see happening a lot today.”

The IndyCar legend’s recollection of Glass closed with a sentence that would frame most of her remaining racing career.

“She didn’t win, but she was competitive."

Glass also learned about her inner resolve during the Manzanita race. A nasty crash, while attempting an outside pass on the half-mile oval, pitched Glass into a gravity-defying barrel roll at 120mph.

"The back end got loose, slid around, smacked the wall and climbed a 20-foot fence," Glass told the late and revered Los Angeles Times racing reporter Shav Glick. "The car started rolling along the fence. Thirteen times it went over and then it dropped back on the race track and tumbled end-over-end three or four times. The reason I know the numbers is because I've seen the tapes so many times in slow motion.

"All the blood vessels were damaged in my eyes, and I couldn't see for several hours. It damaged all the soft tissue, muscles and ligaments in my body. Unfortunately, they aren't very good at fixing things like that. It really messed up my face, head, neck, back, shoulders and knees. I've had four knee operations trying to repair the ligaments."

At 18, already excelling in college, and with a small business to run, Glass was given the perfect excuse to leave racing behind. Those options, as she told Glick, were never considered.

"Once I realized I was still alive after all the bouncing around, I never doubted I would race again," Glass proclaimed.

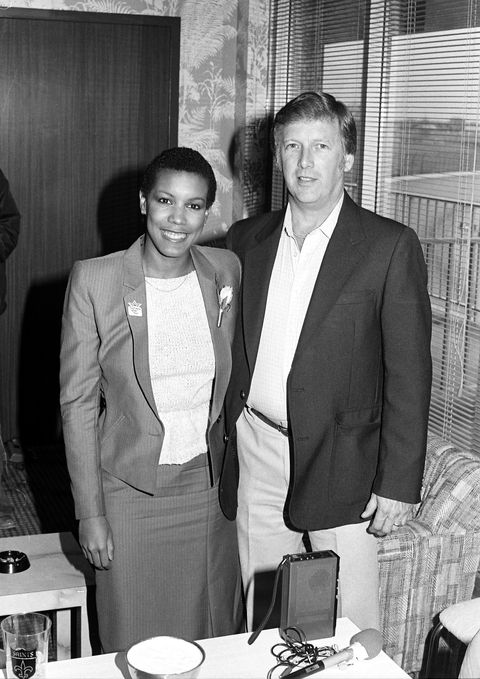

Glass with Charlie Patterson

Courtesy John Mahoney

When she recovered, she ran more sprint car training in Florida, but there was only one place where the best of the best plied their trade. A call from the Midwest in 1982 to drive for Charlie Patterson at the Hoosier Hundred—in the heart of sprint car racing’s fiercest battle ground—was the next big opportunity for Glass.

The USAC Silver Crown field, screaming around the big one-mile dirt oval at the Indiana State Fairgrounds in Indianapolis, would present the 20-year-old with her greatest test as a driver.

Pure animals, from Gary Bettenhausen to Sheldon Kinser and Larry Rice to Bill Vukovich were on the grid, all bred in sprint cars and Indy cars. Glass would need to tame 24 hardened beasts on a wickedly fast oval to send her career into orbit.

“I’ve been involved in racing since 1958, and as the years went by, I’d had a Silver Crown car for about 20 years and thought it would be neat to do something different than hire one of the big names to drive the car,” Patterson said.

“I’d been reading about her and all the wins she’d had up at Skagit Speedway, and I thought, you know, as a gimmick, I might give it a try. I called her up, and she and her dad thought it would be a good idea.”

Patterson, a self-styled talent spotter, hoped Glass would bring attention and corporate dollars to his modest USAC operation.

“I brought her in, and we went out to the [Indianapolis Motor] Speedway where they were having a [IndyCar] tire test, and introduced her to a lot of people there,” he said. “I tried to get her some sponsorship, and that didn’t work out, but I had a business, Patterson Driveshafts, and did it out of my pocket.”

Veteran IndyCar and dirt racing reporter Robin Miller attended the IMS press conference where she and Patterson announced their USAC plans. As Miller wrote in the Indy Star, he found Glass to possess the same kind of bravado that emanated from within the Midwest sprint car crowd.

“I am a front-runner, I plan to finish in the top 10,” she said of her Hoosier Hundred plans. “I picked sprinters because they are the biggest, meanest, roughest cars that I could drive to make a name and go on.” Reaching the 1983 Indy 500 was her ultimate goal.

Far removed from Skagit Speedway and the other venues she’d mastered against lesser competition, Glass was humbled by the USAC heroes. Think of the high school quarterback, the best in the district, being overwhelmed as a college rookie against the best the nation has to offer. That was Glass’ reality at the Hoosier Hundred.

Miller watched her run at the fairgrounds and instantly recognized the mismatch in experience and aptitude.

“You don't throw someone into a sprint car on a mile track when all they've ever done is little quarter- and half-milers,” he said. “That's insane. I thought it was unfair to the kid.”

Courtesy John Mahoney

To her credit, Glass was able to run faster than a few drivers leading up to her race, but still ranked among the slowest at the event and was moved to the back of the field for the start. According to Patterson, once the Hoosier Hundred got under way, Glass would make a few passes before pulling in and retiring nine laps into the 60-lap feature race due to severe handling problems.

“She said, ‘I just can’t drive this thing,’” he remarked. “She was struggling with the car jumping the cushion, so we parked it. That was the last venture we had.”

Despite the odds, Glass made the field and was credited with 21st-place after her early exit. Patterson speaks of the achievement with pride.

“It gained a lot of national notoriety,” said the 80-year-old. “It was the first time a girl did that well in a Silver Crown car. And she was a black girl, too, which added a lot of charisma to it. We conquered some space there that no one had ventured.”

Glass broke barriers at the fairgrounds in 1982. That part is undeniable. The trip to Indiana was also incredibly revealing. Few would accuse Patterson of having the best car for Glass to use in USAC, but her limitations in the Hoosier Hundred weren’t attributable to the yellow sprinter she drove.

Having learned the same lessons during his own attempts to compete against the same USAC heroes, Miller had been down the road Glass found at the fairgrounds: She wasn’t good enough to race wheel to wheel with the greats. Not at 20 years old, and not against elite drivers who’d been racing longer than she’d been alive.

“Midgets, sprints, dirt cars—this is where you went to make your name, and it was a melting pot of talent,” he said. “There were a lot of really talented drivers like her who came from the west coast to take on the best and found it was a whole different world. There were a lot of drivers like her that packed up, went home, and never came back.”

Patterson agreed, and raised an item that would be mentioned by others in subsequent interviews about her career in its latter stages.

Initially buoyed by the opportunity to test herself at the Hoosier Hundred, Glass’s demeanor took a turn for the worse as the USAC event got rolling. Given her inner drive, it’s easy to envision Glass bristled at the idea of being a backmarker. Especially after owning the oval scene at home. It’s also likely that as one of one, she felt the pressure to positively represent her family, gender and color on such a big stage.

Racing’s simplistic measuring process—you’re either fast enough or you aren’t—told Glass and all those in attendance where she stood in the big leagues.

She could make it into the show, but was not capable of posing a threat to the established stars. Although her father Marvin was at the race—a warm and friendly man set within a towering frame, Patterson cannot recall his driver finding comfort in his presence.

Glass in 1984

IMS

“Her biggest problem was her attitude,” he said. “She seemed to be down on herself and down about everything. She was not a very joyous person at all. She was out of her element, and her attitude was partly because I don’t think she realized how big a step this was until she made the step. I think her attitude hindered her more than her lack of experience.”

In time, it’s possible she could have risen to the challenge, but her life in sprint cars was brought to a quiet end. Another route to the Indy 500 would need to be found.

Glass would eventually trade sprint cars for road racing where, as a complete novice, a brief foray into the SCCA Can-Am series in 1984 did little to move her closer to the Brickyard. An attempt to run in the burgeoning Mickey Thompson Off Road series in 1985, where Baja 1000-style trucks were raced at indoor arenas, was remembered as another setback when Glass nosed over and had to be cut out of the high-flying vehicle. With a replacement race truck sourced for the event, a second crash ensured the off-road experiment would come to an immediate stop.

To get his daughter’s Indy 500 dream back on track, Marvin Glass purchased an old Penske PC6 Indy car for Cheryl to test at Seattle International Raceway. Contained within a beautiful forest, the combo drag strip/road course wasn’t the most demanding circuit, but it was the best Washington had to offer.

It’s unclear how much time Glass spent in the aged Indy car chassis, but her confidence, something Glick described as “remarkable self-assurance for one so lacking in experience,” stood out during their 1985 interview.

"I expect to be at Indianapolis in two years," she said. "I am confident of my ability. I think I have shown what I can do in a race car and I hope to have an Indy car team next year to condition myself for the [Indy] 500. I don't want to jump into it before I'm ready, but if I run most of the CART [IndyCar] series in '86, I should be there in '87."

Those Indy 500s, and more, came and went without her name on the entry list. Racing would take a backseat while she established Cheryl Glass Designs, a custom gown and wedding dress business, located in downtown Seattle. Building her company, modeling, and involvement in a forerunner of today’s Science Technology Engineering and Math (STEM) education programs for inner city students, accounted for a significant portion of the time leading up to her Indy Lights debut.

Aided by Hersey Mallory, a well-known team member with the championship-winning Electramotive Nissan IMSA GTP program, Cheryl Glass Racing bought a car and entered the penultimate round of the 1990 Indy Lights championship in Nazareth, Pa.

Cheryl Day Anderson

The paved one-mile oval, where she’d pilot the March-Buick chassis with its 420hp V6 engine, wings, and slick tires, was the perfect venue for Glass. Robbie Groff, who went on to win the Nazareth race, saw her struggling in practice. The Californian, along with his older brother Mike, had known and raced against Glass since they were kids, and stepped in to provide Glass with invaluable chassis setup information. It turned the red and white No. 18 from a diabolical opponent to a friendly ally.

Qualifying ninth in the 11-car field, Glass still wasn’t particularly fast, and came home nine laps down to Groff in the 75-lap contest, but she put her oval knowledge to use and recorded a seventh-place finish. After the race, she told IndyCar Racing magazine there was an obstacle to overcome inside the cockpit.

“My biggest problem came from yesterday when the fire bottle went off,” she said. “I’ve got first and second degree burns on my leg. Every time I lifted or got on the gas, I aggravated the burns.”

Glass shared her open enthusiasm for the next challenge, the Indy Lights season finale in Monterey, Ca.

“I really love this series,” she continued. “Everyone has been so nice and helpful with getting our car set-up. I’m going testing at Willow Springs before Laguna Seca. That extra seat time will help out a lot.”

That optimism would soon be replaced by dejection.

After crawling around Laguna Seca’s winding, hillside road course with lap times more than 10 seconds off the pace, Glass was in clear jeopardy of failing to qualify for the race. At a road course like Laguna Seca, where immense skill in the discipline is required to succeed, Glass embarrassed herself.

Unlike her gradual move up the dirt racing ladder, she attempted to bypass the massive open-wheel learning curve by jumping straight to Indy Lights. Once more, Glass was met with a reality that didn’t fit her inner narrative. Many things in life came easy to Glass. Outside the ovals, ease was nowhere to be found.

In contrast to the top Indy Lights drivers, the Paul Tracys, Robbie Buhls, Eric Bachelarts, and others who’d gotten their start in road racing around the same age Glass began her pre-teen oval journey, there was no hope of bridging the competitive gap. Not without years of training.

Willy T. Ribbs, who would go on to break the color barrier at Indy in 1991, was racing at Laguna Seca that weekend. He’d started his IndyCar career early in the 1990 season, and by the finale in Monterey, the San Jose native was finding his stride. Mario Andretti and Rick Mears didn’t have to worry about losing their jobs to Ribbs, but he still settled into a solid mid-pack groove late in his rookie campaign.

Cheryl Day Anderson

As the most famous African-American race car driver in the world, and a trailblazer in the series she wanted to reach, one might have expected Glass to find Ribbs at Laguna Seca–his home track–and seek road racing advice. Or, possibly, to ask for insights on how to advance her career as a person of color in a new and unfamiliar form of racing.

Oddly, they only met by chance, because of Ribbs, and it was a very brief encounter.

“I was leaving at the end of the day, and me and my publicist were riding out of the paddock, and I saw her standing out by her tent, stopped the car, got out and introduced myself,” Ribbs said. “She said she was trying to learn how to drive road courses, and I told her whatever help she needed, to let me know. That was it. The conversation lasted maybe three minutes. She didn’t have much to say.”

Marshall Pruett

Sullen and withdrawn, Glass left Ribbs with the same type of impression Patterson described after the ill-fated USAC race. Ribbs’ open-ended offer to help was never acted upon.

“That’s the first time I met her and the last time I saw her,” he added.

Glass, as expected, failed to qualify at Laguna Seca.

As a black man in professional road racing, Ribbs knew what it was like to be one of one. Recognizing her unique position in the sport, he was drawn to her plight.

“There’s more chances of a black woman being an astronaut than being in a race car,” he said. “I knew who she was before I met her, knew she’d run sprint cars, and knew there’d been none like her before and there’s been none since. A black woman will be president of the United Stated before another Cheryl Glass comes along.”

Carrying a vibrant new paint scheme, the No. 18 Cheryl Glass Racing March-Buick would return for the 1991 Indy Lights season opener. Starting last on the street course at Long Beach, Glass would complete 14 of the 45 laps and finish 17th out of 18 entries. Electrical problems were listed as the reason for the failure to finish.

Moving to the one-mile Phoenix oval the following weekend, Glass was back in her comfort zone, yet only qualified 14th in the 15-car field. In what would prove to be her final race, Glass crashed 30 laps into the 75-lap contest and finished 14th.

Cheryl Day Anderson

If Glass was forced to bid farewell to her Indy 500 aspirations that day in April, the rest she forfeited during the final six years of her life carried a much heavier price.

In August of 1991, her home was burglarized by three men while she was sleeping. A swastika and Nazi propaganda was drawn on the wall using lipstick taken from her purse.

"I'd rather have someone burn a cross in my front yard than have them come into my home," Glass told the Seattle Post.

"I have never seen anything like it in my 12 years," added police spokesman Rob Barnett. "But I would say they were [committing] a burglary."

After the initial robbery was reported, Glass returned to the police department to state she’d been raped by two of the burglars during the home invasion. According to the Seattle Times, “authorities said there was insufficient evidence to bring charges.”

This is the point where Glass’s life began to fall apart.

Turned away by the police on the rape allegations, her actions after August 1991 speak to a person fighting to be taken seriously and fighting for justice. And, possibly, fighting for her safety.

Numerous reports of incidents with the police, including allegations of being beaten by members of King County law enforcement, fights with her neighbors, arrests, restraining orders against her neighbors, a curious car fire with her personal vehicle, and a lawsuit against the police fill a frenetic timeline for Glass from 1992-1996.

With so many unresolved questions, the turmoil that marked her post-racing life met its end, 20 years ago this week, in Lake Union.

Patterson, along with Cheryl’s mother Shirley, met for the first time last year when Glass was honored at the Sprint Car Hall of Fame in Knoxville, Iowa. Mrs. Glass was forthright in her opinion on whether Cheryl committed suicide.

“Her mother told me, ‘Charlie, never ever think that she jumped off that bridge to kill herself. She was thrown off that bridge,'" he said. “I said I’d never given it a lot of thought, but figured maybe her life got to a point where she couldn’t handle it, and she said, ‘not on your life. Somebody had to throw her off that bridge.’”

Glass wasn’t destined for greatness as a race car driver; not outside the Pacific Northwest, at least. But that doesn’t diminish her contributions or importance. Not as one of one. The same could be said of Ribbs. A devastating force in sports cars, that same degree of greatness proved elusive behind the wheel of an Indy car.

Decades later, for both drivers, I’m no longer sure it matters.

“She was remarkable, let alone being a strong racer where she lived,” Ribbs said. “Look, I know how hard it is trying to break into this sport. And her, in those little ovals where she raced? That’s where my respect came for her. She had the guts, times three.

“One, for her to take on the bullrings where she raced, and two, as woman when women weren’t doing what she did, and three, as a black woman, and there wasn’t anybody like her around? She was doing this while Barack Obama was still in high school, man. I’m serious. She was way ahead of her time.”

Cheryl Linn Glass, gone at 35. She would have turned 55 in December.

#654

Posted 30 September 2017 - 03:35

#655

Posted 03 October 2017 - 15:17

Robert Yates 1943-2017

Monday, 02 October 2017

By Kelly Crandall / Image by Jon Ferrey/Allsport & ISC archives/Getty Images

NASCAR Hall of Fame inductee, championship car owner and engine builder Robert Yates has died at age 74.

"It is with heavy hearts that we announce the passing of our founder, Robert Yates, who was a leader and legendary NASCAR figure," a statement from Roush Yates Engines said. "Robert passed away peacefully on the evening of Oct. 2, 2017 surrounded by his family and loved ones. His light and passion will always lead us."

Yates had been battling liver cancer since October 2014.

Rising from an engine builder with Holman-Moody Racing in 1968 to a car owner, Robert Yates Racing was one of the most recognizable organizations in the sport. Yates fielded cars for drivers such as NASCAR Hall of Famer Dale Jarrett, Davey Allison, Ricky Rudd and Elliott Sadler among others. As a team owner from 1989 to 2007, Yates' teams earned 48 poles and 57 wins, including three in the Daytona 500. The first came in 1992 with Davey Allison, who won 15 races for Yates. He also won both the Coca-Cola 600 and the Brickyard 400 twice.

In 1996, his operation grew to a two-car team with Dale Jarrett and Ernie Irvan, with Jarrett earning Yates' second Daytona 500 win that same season (and his third in 2000). Jarrett also delivered Yates his first and only car owner title in 1999. He retired in 2007 and handed over the operation to his son, Doug Yates.

Yates’ legacy will also include his accomplishments as an engine builder. Building engines for some of the sport’s biggest names, Yates powered NASCAR Hall of Famer Bobby Allison’s championship season in 1983. As an engine builder, Yates scored wins in the 1962 and 1982 Daytona 500s. He was also the engine builder for NASCAR Hall of Famer Richard Petty’s 199th and 200th victories.

A partnership with Jack Roush and Ford in 2003 led to the formation of Roush Yates engines. To this day, the company continues to supplies engines to all Ford-back entries in each of NASCAR’s national divisions.

“Robert Yates knew the value of hard work and earned everything he achieved in life,” said Dave Pericak, global director, Ford Performance. “Not only was Robert a legendary engine builder and championship car owner, but he was a husband, father, grandfather and loyal Ford man who left an unmeasurable impact on those who knew him.

“He was a respected and valued member of the Ford family and co-founder of Roush Yates Engines, and while we’ll miss the wisdom he possessed for working on engines and race cars, we will miss his caring demeanor and friendship even more. Our thoughts and prayers go out to Robert’s wife, Carolyn, his two children, Doug and Amy, and his eight grandchildren.”

Three times in the last five years, he barely missed the cut for the NASCAR Hall of Fame. But his name was the first one called by NASCAR vice chairman Mike Helton for the 2018 class.

"Right now, I feel like I could take a jack and jump over the wall and I'd be on the right side [of the car] like I used to be," said Yates at the Hall of Fame annoucement. "I don't even know if I'll sleep tonight. I'm so honored."

On Labor Day weekend, Stewart-Haas Racing honored Yates with a throwback paint scheme on the No. 10 of Danica Patrick, resembling the No. 88 Quality Care car Dale Jarrett drove for Yates from 1996 through 2000.

"I'm pulling for Danica to do something outstanding there," Yates said of the Sept. 3 race. "I've always pulled for her. And in the respect of some people saying she doesn't deserve to be out there, I stand up and advocate for her.

"I hope she wins. I hope she makes (everyone) completely wrong and she's come close to it. I pull for her."

#656

Posted 04 October 2017 - 12:58

Na danasnji dan pre 25 godina vozeci na trci Bathurst 1000 od posledica srcanog udara preminuo je svetski F1 sampion za 1967. novozelandjanin Deni Halm.

When Jack Brabham took Denny Hulme on as a mechanic in 1961, he couldn’t have imagined that Hulme would beat him to the Formula One world championship title six years later. Hulme had driven for Brabham in the junior formulae before graduating to F1 with them in 1965.

In 1967 he won only twice – in Monaco and Germany. But his consistency stood him in good stead against Jim Clark’s fast-but-fragile Lotus 45. With Brabham dropping points on more than one occasion when new parts on his car let him down, Hulme grabbed his chance to become champion.

He moved to McLaren the following year where he remained for the final seven years of his F1 career. He took six more wins but never looked likely to claim another title, although he did fit in a successful Can-Am racing career alongside his F1 activities.

He resumed racing in the 1990s, but died from a heart attack in 1992 while competing in the Bathurst 1000km touring car race. He was 56.

#657

Posted 05 October 2017 - 16:49

#658

Posted 10 October 2017 - 01:02

Bill Puterbaugh 1936-2017

Monday, 09 October 2017

Robin Miller / Images by IMS

Bill Puterbaugh, who once qualified in the dark trying to make his first Indianapolis 500 and then came back to be rookie-of-the-year in 1975, passed away Monday at the age of 81 in an Indianapolis hospice.

A burly sprint car driver that came from IMCA to USAC in the late '60s, Bill and was given his initial opportunity at IMS in 1968 when USAC refused to give Danny Ongais a license. It wasn't a vary good car, but it was Indy and it was a chance. As rain shoved Bump Day later and later, Bill Cheesburg and Puterbaugh were given the option of going out when the brightest things appeared to be the scoring tower light (below). They both opted to qualify, but their speeds were too slow to make the field – which was filled on Monday.

Puterbaugh tried unsuccessfully for five more Mays before finally landing a decent ride for 1975, when he qualified 15th and finished seventh to earn ROY. He also qualified the next two Mays, but there was some drama in 1977. He put Lee Elkins' Eagle in the show but the day after time trials he was told Salt Walther (who missed the show) had a backer to purchase Putt-Putt's car. A firestorm of bad publicity broke out for Walther, who wound up watching the popular Puterbaugh finish 12th.

Bill is survived by wife, Joyce, and son, Billy.

#659

Posted 13 October 2017 - 21:02

#660

Posted 16 October 2017 - 21:24